Pat Passlof: Paintings from the 1950s

Elizabeth Harris Gallery, New York

October 16 – December 20, 2014

A must-see show of early works by Pat Passlof is on view at Elizabeth Harris Gallery, New York through December 20. Organized in conjunction with the Milton Resnick and Pat Passlof Foundation, this exhibition charts the earliest years of Passlof’s career from her studies with Willem de Kooning to her first exhibitions at the historic, artist-run March Gallery on Tenth Street. Passlof’s paintings from this period tell the story of a talented, audacious painter coming of age during a legendary decade of New York painting.

Passlof began the decade as a student, and one cannot discuss her paintings of the 1950s without addressing the influence of her teacher Willem de Kooning. After seeing an exhibition of de Kooning’s work at Charles Egan Gallery, Passlof sought his instruction, first at Black Mountain College and later as a private student in New York. 1 Tasked with “tightly rendered still lifes,” 2 Passlof embraced abstraction on her own as “a form of insubordination.” In her own words, she “took to abstraction like a feather to wing” rapidly adopting (and mastering) her teacher’s incisive, whiplash drawing style and his ability to evoke complex spatial architectures while maintaining the integrity of the picture plane. 3 Although the earliest paintings in the show find the young Passlof actively learning from de Kooning’s example (Asheville (1948) and Woman, Wind, and Window II (1950) come to mind), they are utterly fearless in their execution; one senses the student challenging the master at his own game.

The full and open nature of even her most youthful pictures also suggests that Passlof absorbed de Kooning’s belief in a cultured, holistic view of painting. “Spiritually I am wherever my spirit allows me to be,” he wrote in 1951, “and that is not necessarily in the future.” 4 This sense of the timeless nature of art seems to have stayed with with Passlof who consistently challenged her own gift for gestural abstraction against works of the past, and an insistent (if veiled) attention to the world around her.

Passlof later became an influential teacher in her own right. Her reflections on making the difficult leap from student to independent artist shed some light on her early experiences as a painter:

“Here’s the problem: it is as if there is some kind of magic cloak. Every aspiring artist is eager to don this garment, which proclaims: I am no longer a student or apprentice; I am the thing-in-itself, an artist. The moment the student locates this mythological wrap and flings it around the ego, he or she cries out in pain. The shapeless thing appears to be lined with thorns, so that, as you draw it around, real psychological and spiritual blood flows…”

“Now, if you decide to keep this prickle to you, eventually, some of the tips do break off and become permanently embedded, the pain internalized. A secondary problem then arises concerning the ‘fit.’ What kind of garment is this? Does it have sleeves, legs, perhaps feet? These are difficult to determine, then to locate, then to differentiate. More difficulties: which is the front, which the back? Is it right-side-up or up-side-down? Why the obscurity? Because the cursed thing is forming and changing as you work: shaped and changed by the work.” 5

This shaping and changing can be seen in Passlof’s work throughout the 50s. Scanning the gallery one sees how she thoroughly explored her mentor’s influence, then left it behind. Many paintings from the early to mid decade read as abstracted still lives. One senses the artist testing those “tight” still lives assigned by her teacher against her growing knowledge of gestural abstraction. The paintings never look simply “abstracted from,” rather they seem to be free explorations of possibilities. A long look at Coliseum (1955) suggests that its development may have moved both towards and away from representation. In paintings such as Pas de Quatre (1952) forms feel solid even as their specific identities are in flux. In another untitled painting, individual forms fuse entirely into the language of paint. A Soutine-like urgency emerges.

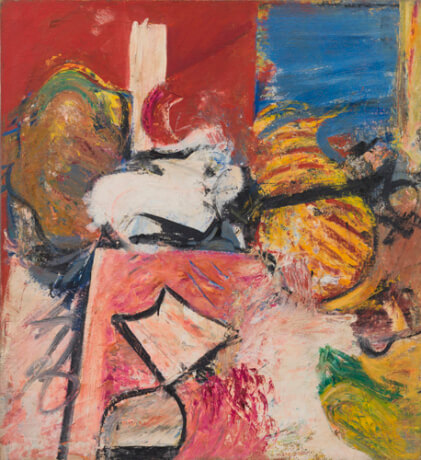

Both Ionian (1956) and Spire (1958) are readable as studio interiors. In them one sees her pitting the all-over gestural approach of Tenth Street painting against the color and light of Matisse – or is it the other way around? Either way, her effort is heroic, resulting in visually dynamic pictures. An open window spatially anchors each painting, hinting at Passlof’s burgeoning contemplative vision. This outward-looking tendency in her work separates her from many New York School painters including her husband Milton Resnick, whose use of paint, though similar, was more meditative and inward in nature.

In Passlof’s large works from 1958-9, the referential quality of her brushstrokes and a particular, dappled light confirms her interest in sources outside the paintings. Although the window is gone in Lookout (1959), Stove (1959), and Promenade for a Bachelor (1958), the paintings are suffused with natural illumination. In a later interview Passlof remembered that the demolition of the “El” in the late 50s flooded the neighborhood with light. 6 The artist also fondly recalled the story of a pigeon that frequented her studio via an open window. One day the bird flew into the painting that would become Promenade for a Bachelor. Passlof promptly cleaned off the bird and continued the painting, retaining the bird’s energy and movement in brushstrokes that hover and float. 7

In all three of these pictures, there is a palpable sense of lifting. Gallerist Elizabeth Harris notes that Passlof often spoke of courting this sensibility, referring to it as “aspirational space.” This rising space feels particular to Passlof. Breaking from the lateral expanse in much Abstract Expressionist painting, its precedents include the spaces inhabited by El Greco’s flickering saints, Tiepolo’s spiraling heavens, even the upward gaze of Guido Reni’s Magdalenes. An “X” hovering at the top right of Stove, recalls the crossed forms (and placement) of the angels in Titian’s Europa and anticipates Resnick’s late X-space paintings.

It is interesting to note that as Passlof’s palette changes, a lighter, more lyrical touch appears in Resnick’s work of ‘58 and ‘59. So clearly sourced from the light filtering into her studio, Passlof’s paintings of this period suggest the influence here was hers.

In addition to the almost cinematic presentation of a young artist’s development from student to professional, this exhibition (as Raphael Rubinstein notes in the show’s catalog essay) also provides an invaluable, focused view into the world of Tenth Street painting. An American Montmartre, the Tenth Street milieu remains, nonetheless, relatively opaque. In the presence of Passlof’s paintings, however, one can slip into a daydream visit to the March Gallery. There is a day-in-day-out sense of discovery and wonder in Passlof’s 50s paintings, an ethos that bears out the hazy romantic view of an era that produced so much celebrated American painting.

And yet, this heroic decade of painting was primarily the realm of heroes, not heroines. Female artists including Passlof were marginalized. She noted that women artists, even respected ones, were still expected to be “nestmakers.” 8 Despite her obvious ambition, Passlof admitted she never thought of a career for herself until she was asked to participate in the March Gallery. 9

Her work, however, defied this marginalization. Painting with strength and authority, she challenged the achievements of her male counterparts as much as she respected and incorporated what she learned. For all their visible influence, her quest for her own vision was aggressive and vital at every turn. Passlof never submitted to influences, she owned them. In doing so, she set herself on the path to becoming a significant painter of the New York School.

Notes

1 Eleanor Heartney, “Tightening the Net: The Paintings of Pat Passlof,” Pat Passlof Selections 1948-2011, Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center, Fine Art Museum Western Carolina University, 2012, p. 2.

2 Heartney, p. 3.

3 Geoffrey Dorfman, Out of the Picture, Milton Resnick and the New York School, Midmarch Arts Press, 2003, p. 277.

4 Heartney, p. 3.

4 Willem De Kooning, What Abstract Art Means to Me, The Bulletin of the Museum of Modern Art, Vol. 18, No. 3, (Spring, 1951), p 7.

5 Pat Passlof, “A Real Syllabus,” Pat Passlof Selections 1948-2011, Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center, Fine Art Museum Western Carolina University, 2012, p. 63.

6 Dorfman, p. 283.

7 Dorfman, p. 307-8.

8 Dorfman, p. 304.

9 Heartney, p. 3.