The gallery displaying American art at the Honolulu Museum of Art is small; it’s attached to a larger gallery displaying African, Pacific and North and South American Indigenous art, itself dwarfed by galleries devoted to the arts of India, China, Japan, Korea, Indonesia and the Philippines. Yet the twenty or so American paintings on display offer a remarkably seamless, succinct history of American painting. From a severe pair of portraits by the colonial painter William Jennys on the far end of our history to a Josef Albers square on the near end, the gallery illustrates an economical story of American statehood.

Hawaiian statehood, of course, is of particular relevance to many visitors of the museum, and a large gallery in another wing is devoted to the arts of Hawai’i. But in the American gallery Hawai’i’s chapter in the story of American history comes in the form of Volcano, c. 1915, by Lionel Walden (1861-1933), which puts the uniquely Hawaiian phenomenon of bubbling volcanic magma in place alongside Albert Bierstadt’s Yosemite Valley and George Innes’ bucolic Passaic. The wall text next to Volcano identifies Walden as a member of the “Volcano School,” a group of painters who, from the 1880s until the early 1900s, created nighttime scenes of the active Mauna Loa and Kilauea volcanoes for an awe-inspired American public. As a piece of cultural history it reminds us that manifest destiny was not just a sprint from coast to coast, but a full-fledged triple jump over land and sea that gave us our 49th and 50th states.

This gallery makes explicit what looks obvious written out on the page: American painting expanded as the country did. Portraiture was the great art form of Colonial America, and Jennys’ portraits of Colonel and Mrs. Joseph Platt Cooke, a flinty pair who defended their Connecticut town in the Revolution, should be entered into the historical record as evidence of why the redcoats ran into trouble on our shores. Nearby is a surprisingly sensitive portrait of a young girl by Charles Wilson Peale, a Son of Liberty—and father of an artistic dynasty—who painted virtually all the heroes of our young republic. Once the likes of Peale, John Singleton Copley and Gilbert Stuart (both of whom can be seen in a portrait gallery downstairs) captured our early statesmen under amber washes of varnish, prosperous Americans took a liking to the still life, a symbol of the newfound security of our growing wealth. Peale’s son James was known for the genre, and his still life here, along with William Michael Harnett’s, exemplifies just how difficult it was for American painters to get off the blocks, artistically speaking, in comparison with Europeans, who seemed always to be in mid-stride. (We never did end up with a Claesz or a Chardin.)

The pictures that would make Harnett famous were of dead game hanging alongside the accoutrements of the hunt. Americans of the mid-19th century had, like their European counterparts, developed a romantic infatuation with the outdoors. As popularized by the high achievements of the Hudson River School, the romantic strain in American painting dovetailed with the moralizing westward expansion of manifest destiny. It was in such a climate that east coast artists sought out new subjects in the west, resulting in works like Albert Bierstadt’s In the Valley of the Yosemite, c. 1872 and Thomas Moran’s The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, Wyoming, 1904. In this context hangs Volcano, an image of a place whose geographical isolation was of scant protection against the American expansionist drive of the late 19th century. When Bierstadt got to Yosemite, in 1863, California was more than a decade into statehood. When Walden got to Hawai’i, in 1911, it too was American territory. More than a decade had passed since the fall of the Hawaiian Monarchy.

* * *

I had been thinking about the relationship of American painting to the American landscape for a steady month before walking into the Honolulu Museum. The extended version, prompted not by a progression of artworks but by a progression of landscapes, played out in my head over the course of seven days as I drove from southeastern Massachusetts to Los Angeles, where I would deposit my car in Long Beach for the sea passage to Hawai’i, where my family would be moving.

If a gallery full of landscape paintings makes one yearn for the places they depict, day after day of driving through the country at 80 miles per hour makes one thankful for the efforts of painters who actually succeeded in locking down the essence of particular places. I kept audio notes as I drove, so I know where I was as particular qualities of the American landscape cued the works of dozens of painters, past and contemporary, in my mind’s eye.

I thought about the ways in which painters had done justice to places, and the ways in which they had failed. I thought about detail and how it could allude to the expansive, as in the case of Charles Burchfield’s weeds and flowers, and of the expansive and how ineffable it could be, as in the case of the Hudson River painters. At Niagara Falls I thought about Frederick Edwin Church, among others, and how good the Hudson School painters were with light but poor at depicting the sheer force of nature, in comparison to modern painters like Marsden Hartley. Though once I got west, I had to concede that painters like Church really had captured the cinematic qualities of our country as well as any moviemaker who would follow in their footsteps.

I was keyed into the topography of my drive, but also the experience of driving, and I thought of a passage by John Berger in Bento’s Sketchbook, in which he likens driving a motorcycle to the act of drawing: “The parallel fascinates me because it may reveal a secret. About what? About displacement and vision. Looking brings closer.” And, later: “You pilot a bike with your eyes, with your wrists and with the leaning of your body. Your eyes are the most importunate of the three. The bike follows and veers towards whatever they are fixed on. It pursues your gaze.”

As I drew my own line through space, I noticed the road. 3,500 miles of painted highway lines disappeared into my dashboard, and I thought of Robert Penn Warren’s hypnotic opening image in All the King’s Men:

You look up the highway and it is straight for miles, coming at you, with

the black line down the center coming at you and at you, black and slick

and tarry-shining against the white of the slab, and the heat dazzles up

from the white slab so that only the black line is clear, coming at you with

the whine of the tires . . .

I noticed farmland more than wilderness, and I latched onto farm buildings; their relationships to the land they sat on and their relationships to each other. American farm buildings sit in perfect harmony with their surroundings. Their placement, in aesthetic terms, cannot be improved upon. I wondered if criteria for judging the aesthetic qualities of the landscape have ever been enumerated, the way each generation of critics is obligated to do for painting. I thought about the vista preservation statute in the creation of Adirondack Park in the early 1970s and of the engineer and surveyor who purportedly drove around for a couple of days looking for “scenic” views to preserve. Their aesthetic preferences were eventually codified into law. What had been the basis of their judgements? I considered the British art historian Michael Baxandall, whose Painting and Experience in Fifteenth Century Italy I had recently read, and I wished that someone with such knowledge and insight had turned his efforts toward a systematic analysis of the landscape. What if there was a corpus of works analyzing the components of topographical beauty, the way there is on, say, the spatial and geometric qualities of Piero della Francesca?

At the beginning of my trip I thought a lot about de Kooning, once he got out of the city and really started to make sense of place, beginning with the Parkway paintings of the late 1950s and continuing all the way to the spare masterpieces he made at the very end. I considered that Long Island had given him his best motifs and that although it’s not part of how people talk about abstract expressionism, his response to that particular environment—the roads and bridges, the light and proximity to the ocean, and his fascination with passing through space—might have given us some of our best portraits of the American landscape.

But by the end of my trip, the idea of de Kooning as the paragon of the American landscape had receded in importance for me, eclipsed by Georgia O’Keeffe. I thought of her often. In relation to the working farms I saw—in Massachusetts, New York, Ontario, Michigan, Wisconsin, Iowa, Nebraska, Colorado and Utah—she was the painter who best captured the beauty and bleakness of their frieze-like facades. I recorded notes about the differences between O’Keeffe’s farms and Grandma Moses’. The latter’s, teeming maps of human activity, are exuberant in the manner of Bruegel; each is a snapshot of all the many moments that might comprise the life of a farm, captured at once. But Moses’ farms were already an idealized version of the past at the time she painted them. Then, as now, the life of a farm visible from the road was next to nothing. Irrigation booms spray water uniformly, pivoting imperceptibly on their axes. Crops stand still. Cows rest. Occasionally, I saw a tractor harvesting a field of wheat or corn, but even this looked inhuman, almost robotic. The solitude of these places is the very essence of O’Keeffe’s farm paintings.

I didn’t pass through New Mexico, but I marveled in Utah, Arizona and Nevada at the way that an O’Keeffe like From the Faraway, Nearby, 1937, could summarize such a variety of physical terrain and exalt the beauty of it all. As I drove, O’Keeffe was the most frequent companion to my thoughts. Somehow she emerged as the most compelling lens through which to see any landscape. As I approached Los Angeles, I recorded a note about my unease that in my new home, Hawai’i, I would surely lack such a lens.

* * *

It was within my first week on Oahu that I visited the Honolulu Museum. Perhaps I was seeking out a link between my new home and my old one. In its American gallery I enjoyed piecing together its version of history. I found other galleries that display significant groupings of American art. The portrait gallery has works by the colonial painter Erastus Salisbury Field, by Stuart, Copley, Whistler, Sargent, Alex Katz and Alice Neel. Another gallery chronicles the leap of modernism from Europe to America, following an excellent collection of works by Cezanne, Gauguin, van Gogh, Bonnard, Braque, Leger, Matisse and others, with an arresting Morris Louis hanging adjacent to works by de Chirico and Tanguy. In this room I found the link I had not known to exist; on the far wall hang three Hawaiian landscapes by Georgia O’Keeffe.

O’Keeffe, I’ve since learned, created twenty Hawaiian paintings in 1939, when she made a nine week visit to the islands at the behest of the Hawaiian Pineapple Company (soon to be Dole), which paid her way in exchange for the use of two images in a national ad campaign. She exhibited the works at her husband’s Manhattan gallery in early 1940, and a number of them are now in the permanent collection of the Honolulu Museum.

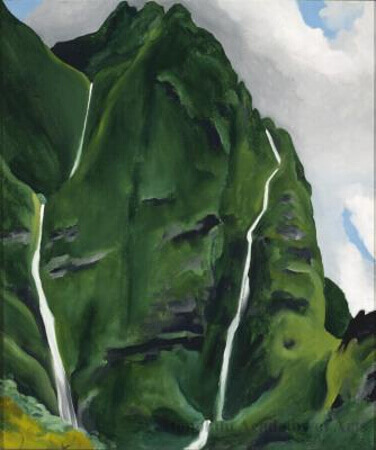

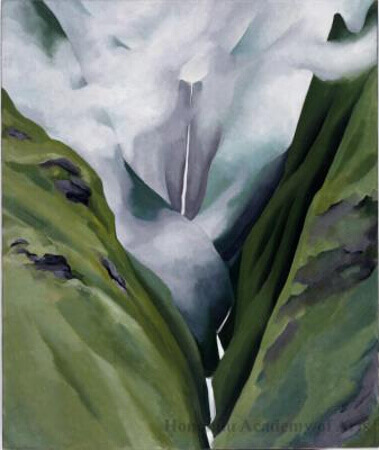

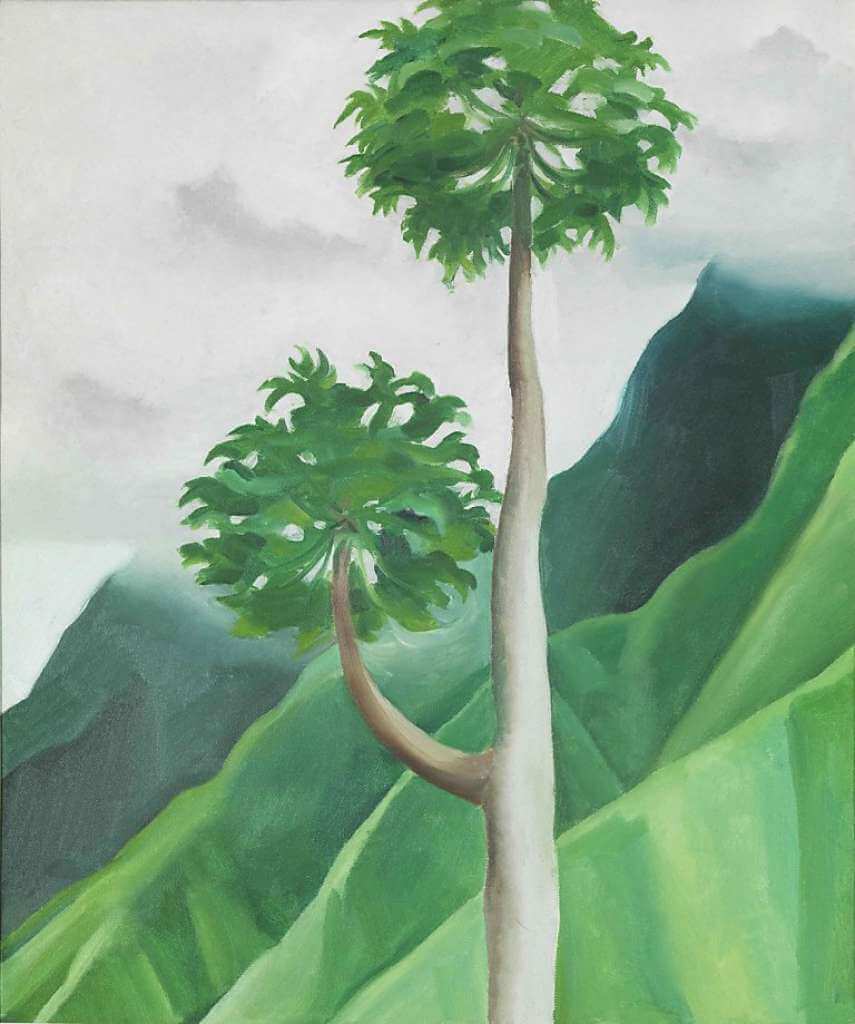

The three that hang there now, Waterfall—End of Road—‘Iao Valley, Waterfall—No. III—‘Iao Valley, and Papaw Tree, ‘Iao Valley, Maui, do for me what the barns of Lake George and the skulls of New Mexico also do: by distilling a place down to its symbolic forms, they subtly but surely allude to a vast range of experiences within that place. O’Keeffe’s Hawai’i subjects are flowers, fish hooks, lava bridges, the waterfalls, the tree, and a lone pineapple, which she grudgingly painted upon her return after Dole had the fruit shipped to her New York studio. The Waterfall paintings revel in a magical phenomenon: despite being located in an area of ocean that gets relatively little rain, the islands’ volcanic spines capture so much moisture that they create some of the wettest places on earth. Just a few minutes of rain can animate a sheer wall of green with elegant cascades of white, articulating the mountains’ structure and depth of field.

In Lionel Walden’s hands the volcano’s presence is subordinate to its treatment as a spectacle. O’Keeffe didn’t treat her subjects as spectacles. Chosen carefully as symbols—she wanted them to stand for more than themselves—she painted them as frankly as she could. As such, her subjects are like prisms; taking form as the focus of O’Keeffe’s intellect, they beam that intellect back into the world in a thousand ways.

* * *

As it so happens, O’Keeffe’s Hawai’i paintings will be the subject of Georgia O’Keeffe: Visions of Hawai’i, at the New York Botanical Garden in the spring of next year. Sounds like just the impetus for a road trip.