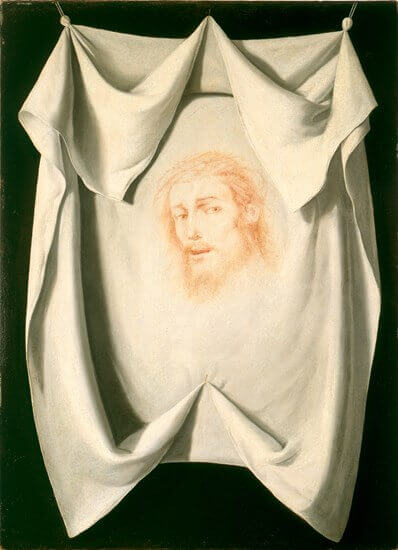

The wall label next to Francisco de Zurbarán’s (1598-1664) Veil of Veronica, c. 1630s, in the Sarah Campbell Blaffer galleries of The Museum of Fine Arts Houston reminds viewers of the image’s iconography: “According to an early medieval legend, a pious woman named Veronica wiped the sweat from Christ’s face on the way to Calvary, and the image of his face was miraculously left on the cloth.” 1 If this account of the story is straightforward enough, Zurbarán’s painting of the veil complicates matters considerably. Part of the complication is in the painting’s seeming juxtaposition of two painterly languages. While the veil itself is depicted with all the verisimilitude that the painter could muster through his trompe-l’oeil technique, Christ’s face, by comparison, appears at first glance to be merely sketched in. There’s a tension in the highly finished treatment of the cloth versus the apparent sketchiness of the face—a tension that calls for some sort of resolution.

Resolution comes with the recognition of the subtle game that Zurbarán has played in this image; rather than paint Christ’s face onto his veil, he has painted a drawing of Christ’s face. Once the image of Christ’s face is recognized for what it is—the painting of a drawing—its status as a bit of trompe-l’oeil verisimilitude comes to light. The vividness with which the painter treats both painted cloth and painted drawing are now in accord. Yet something unusual about the image remains. Why would a sketch-like portrait of Christ end up in place of the ostensible wiped or printed impression of the Veronica legend?

The irregularity of this kind of likeness appearing in this context is heightened by Zurbarán’s unusual decision to present Christ in a three-quarter profile view. Depicting Christ this way, the painter calls into question the means by which the original image has been inscribed onto the veil. Rather than an indexical image, transcribed as a print of dirt, blood and sweat by Veronica or by Christ himself, 2 here Zurbarán presents Christ as he would a studio model, seen and sketched from the painter’s distinct point-of-view. In so doing, the painter shifts attention from the supposed miracle of the image the true likeness of Christ emerging as an impression of his face—to the miracle-like operation of conjuring a likeness through the art of portraiture.

Zurbarán and his studio created a dozen variations on this motif, all of which show Christ’s head in three-quarter profile. In the most recent English-language study of these images widely available online, “The ‘cloth of Veronica’ in the work of Zurbarán,” Odilie Delenda provides the historical context for Zurbarán’s having returned to this theme so often in Counter-Reformation Spain. Delenda writes that in such an environment, “the miraculous imprint of Christ’s features became a statement for the defense of holy or sacred images of the kind criticized and attacked by the Protestants.” Yet Zurbarán’s treatment of Christ’s face in these paintings does more than merely affirm the Catholic taste for images of sacred veneration. In addition to celebrating the right to venerate holy imagery, Zurbarán’s Veils of Veronica also celebrate the tradition of creating such images in the first place, their emphasis on their own making becoming a significant variation within this tradition.

Delenda cites examples of Veil of Veronica imagery made by Zurbarán’s predecessors like Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), Jean Rabel (c. 1520-1603) and Hieronymus Wierix (1553-1619), and such contemporaries as Felipe Gil de Mena (1603-1673) and Domenico Fetti (1598-1623)—all of which portray Christ from a direct frontal position—to demonstrate how unique Zurbarán’s three-quarter profile views are. In depicting direct frontal views of Christ’s face, the icon-like images of these others preserve the essence of the story in which Christ’s image on the veil results as the trace of the act of wiping his face. Presenting Christ face-on, these painters neutralize their own perspective, suspending the truth of the painter-model relationship (Christ’s face seen from a distinct point-of-view) in an effort to adhere to received tradition. Delenda writes:

Realism and a powerful dramatic quality are what most impress the viewer in Zurbarán’s compositions. They show Christ’s foreshortened head with a fine reddish imprint, three- quarters to the right, which was probably closer to the gesture the woman would have captured than what we find in so many hieratic medieval portraits or in the Veronicas of El Greco. Indeed, With Christ carrying the Cross, a front-on portrait would have been nigh on impossible to achieve, an inclined and slightly off-kilter view being much more likely.

Acknowledging that the portrait appears “captured,” as if by a camera, to emphasize the drama inherent in Zurbarán’s approach, Delenda leaves unexamined a further implication of his having depicted Christ’s face from a distinct point-of-view. In portraying Christ this way, Zurbarán imbues his paintings with self-referential commentary on the very means of their own making.

There is a second way in which he does this. In the Houston Veil of Veronica, the reddish portrait is suggestive of red earth or blood wiped from Christ’s face, but equally of the painter’s red-chalk, or sanguine—the medium popularly used in drawings for its earthy and bodily associations. In another of his efforts, the Nationalmuseum Stockholm’s The Veil of Saint Veronica, (c. 1635-1640), we see the painter make use of, almost have to resort to, grisaille in rendering Christ’s likeness on the veil. In both these instances, and indeed in all of his treatments of the motif, Zurbarán chooses not to hide the basic tools of his trade. In place of the frontal treatment of Christ’s face—the preservation of the trace impression—which tradition had handed to him, he inscribes red-chalk and grisaille three-quarter view portraits onto his veils. In doing so it is as if he reclaims the miraculously appearing image for the art of painting.

In the Houston painting, it is through the relationship of drawing to painting that Zurbarán calls attention to two miracles, those of the Veronica legend and of the painter’s art of creation. The trompe-l’oeil of the sanguine sketch, no less than the three-quarter view, continually refers the viewer back to the original tension that I felt in front of the picture, a tension between “finished” painting and “unfinished” sketch. The painting calls attention to the stages of the painter’s labor (drawing comes first, in preparation for grisaille, and finally color) that will eventually bring it to life. Perhaps this is why Zurbarán returned to the theme so often. What better subject than a miraculously appearing image for a painter to test—and call attention to—his own painterly language?

Notes

1 Thank you for comments from Jeffrey McMahon and Stephen Westich.

2 The most recent study on this subject in English available online is Odile Delenda’s “The ‘cloth of Veronica’ in the work of Zurbarán,” Bulletin, Bilbao Fine Arts Museum, no. 7, 2013, pp. 125-161. Here Delenda suggests that in most contemporaneous Spanish understanding of the story, Christ wiped his own face from the veil that was handed to him by Veronica. Delenda quotes the Spaniard Pedro de Ribadeneyra (1526-1611): “Amongst those devout women there was one called Berenice, or Veronica, who gave the veil, or scarf, that she was wearing on her head, to the Lord to wipe away the sweat and blood from His face; and this he did, leaving imprinted on the veil the likeness ad the blood of His Face. . .” and painter Francisco Pacheco (1564-1644): “The second occasion on which our Redeemer made an image of himself was the day of His Passion. . .”