The following essay was written by David Rhodes for an exhibition of paintings by Andew Seto on view at Galerie Vidal-Saint Phalle, Paris from January 8 – February 11, 2015.

In the early 1900s, painting underwent something of a bifurcation. In Paris, Picasso and Braque broke with post Renaissance conventions and radicalized anew the concept of pictorial space. They retained connections to the perceived world and at the same time sought a meditation on the visual language of painting. By arranging angled planes in a shallow pictorial space using a restricted palette, they succeeded in presenting a frontal picture plane that also included multiple points of view, thus opening painting conceptually and formally to further invention and to what became known as abstraction. By 1931 a loose affiliation of artists in Paris, calling themselves Abstraction-Création, followed the innovations of cubism in the direction of abstraction in opposition to André Breton’s Surrealist’s. Leo van Duisburg’s Composition VII (The three graces), 1917 and Kazimir Malevich’s Suprematist Composition (Blue rectangle over purple beam), 1916, for example, had evinced a geometric painting that Picasso and Braque, after their Cubist experiments, choose not to pursue in returning to figuration.

By the 1970s in New York, some artists including Mary Heilmann, Terry Winters, Carroll Dunham, Bill Jensen and Stephen Mueller, were finding the situation of purely phenomenological formalism constricting. In introducing mark making and metaphor these artists reclaimed aspects and implications of earlier moments in the development of abstraction and were able to avail themselves more fully of the discoveries made during Cubism’s heyday. Andrew Seto’s paintings are consonant with this attitude and gain in richness from such a productive impurity. The amalgams Seto explores are exactly placed to move however he desires, each painting relating to and informing the next. There is a high degree of focus in finding images that provoke sublimity and bathos whilst remaining somatic and corporeal.

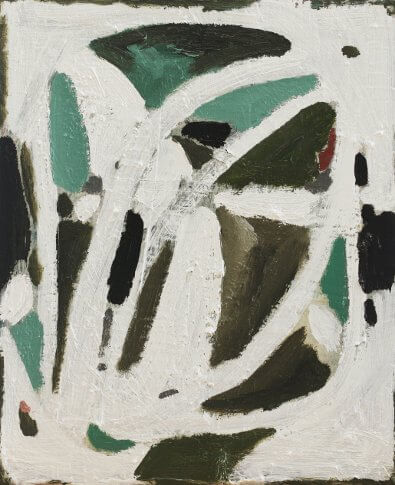

Rigor Mortis, 2014, features a solid looking, yet apparently animated, vertical motif that resists stasis in its awkward twisting accumulation of faceted planes despite the very physical application of greens and blacks. The structure appears to both insert itself into and exist in front of, a pale ground. This ground, if seen as such, is undermined as independent from the figure for two reasons. One, because of an equally physical approach in its painting and secondly, because glimpses of the same colour as the ground and pale spots of other colour partially integrate the structure with the ground. Ambiguities multiply – the form is like an imaginary sculpture, perhaps anthropomorphic and semi-abstracted, or a plant. The title itself suggests a stasis after life – the physical fixity though, is not an imaginative one – long after the painting is finished, it remains visually active – each viewer finding alternative readings, dependent on their particular context. In these ways Seto’s paintings remain open and avoid definitive interpretation.

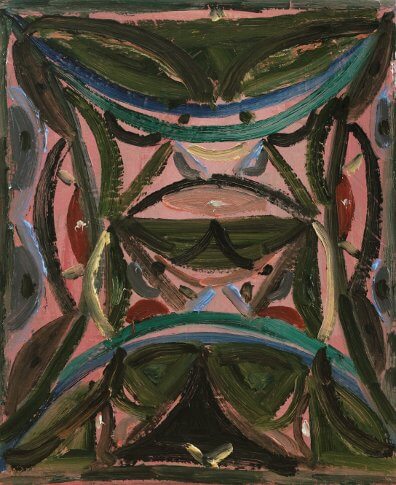

Another painting that references a state of repose with its titling is Rest Assured, 2014. It also has a range of colour, like Rigor Mortis, associated with nature, here in shapes that could also be seen as elements of a still life. Characteristically, the painting bares a build up of paint from a succession of changes – some corresponding to previous compositional moves, others to establishing the composition as it now appears, process and mark making vie with each other. The repetitions that often appear, typically never become a complete field, always remaining variegated. Shapes stack, subtly overlap and abut, implying growth and accumulation, the curves and diagonals establish a lager outline and suggest a dynamism that though it is now at rest, could have continued. The physicality as is usual in Seto’s paintings, is hard won, not facile – the balance precise. A reddish brown can be seen under the olive green that the black contours spread across, indicating that colour, as well as shape, undergoes much revision and transformation during the course of painting. A dark light of slow contrasts rather than sharp steps of brightness define the atmosphere.

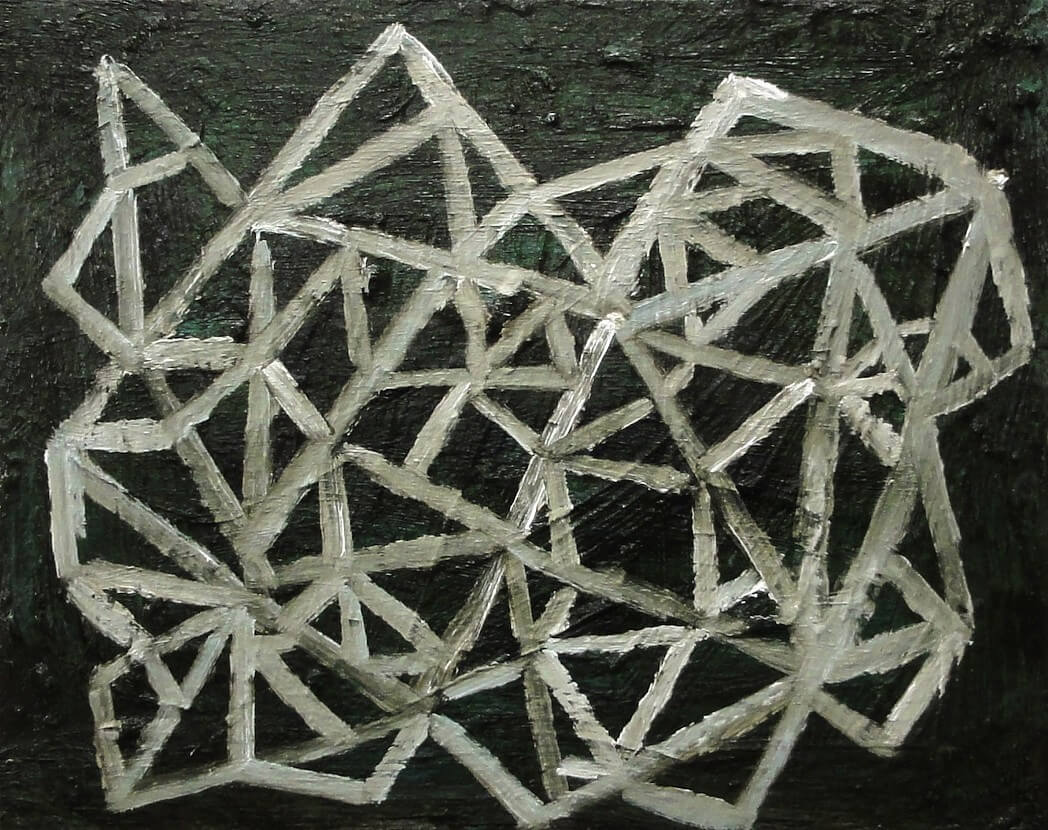

A dirty white tessellated network of lines touch only the bottom side of At Last, 2014 evoking three dimensions despite being almost incised into a knotty, thick and tonally contrasting surface. In multiplying inexactly the small planes created by the direction of the lines raise issues of imperfection, which could easily be either of an organic, or a mathematical provenance. The abraded pattern produced, engages spatiality and references the non-narrative abstractness key to late modernism, take for example, Brice Marden’s post monochrome paintings. Seto’s approach is syncretic in re-introducing figurative elements and expanding metaphorical and allegorical concerns, all without sacrificing abstraction’s non-narrative materiality. The curved ridges of the dark ground, unatuned as they are to the lattice like drawing, resist any simple elegance and add to the already somatic quality of the painting. Contradictions such as this interest Seto. As anomalies only possible in painting, they can carry philosophical thinking forward by means inherent in painting as a specific medium.

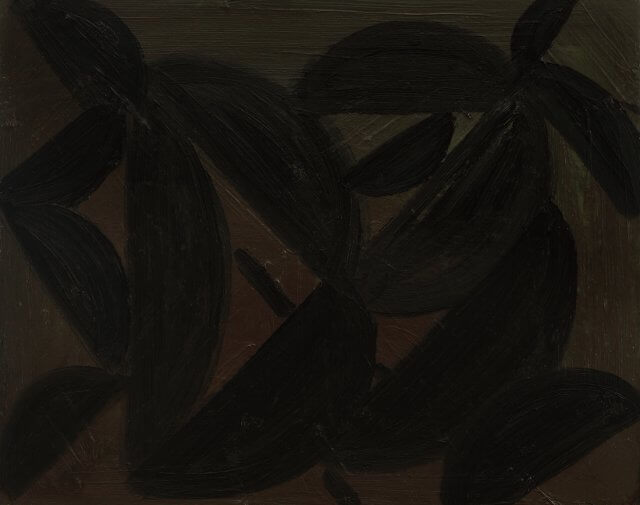

In Smobservation, 2014, a slanting linear armature runs transversely corner to corner, italicizing Mondrian’s familiar format and referring obliquely to, as the mark making is openly gestural, Suprematism. Raoul de Keyser comes to mind, another artist who similarly eschews the categorical limitations often times placed between abstraction and a depiction of things seen. The model of reality that results incorporates imagination and observation, allowing a hybrid image to occur that is closer to experience than language mediated approaches, as touch and sight are retained, as well as thinking and the subsequent forming of words. Small dabs of paint semaphore flickering points of light and seem to work as detail in both a decorative way and as repetitions of the overall structure at another scale, smaller in this case. Perhaps what is implied is the possibility of growth or maybe a simple miniaturization. It could be a system of branches or a grill, a remembered aspect of nature or urban fabric, or it could as easily be a sign or a topographical schema. The grey crisscrossed is as difficult to pin down, is it concrete, fog or cloud? Certainly, it is assertively paint.

Oculus, 2014 – oculus denotes a circular opening in a dome or wall and is taken from the Latin for eye – comprises a recessive space hewn through a matrix of white that interweaves figure and ground, disturbing notions of what came first or last and so moving the temporality backwards and forwards in time. What is denotative and connotative is also combined and shuffled back and forth – the surface facticity of painting with ideas of reflection and shadow in a prismatic space.

Seto’s paintings never completely disavow the natural world for a purely intellectual one, existing instead as an open means of representation situated somewhere between. Traditional qualities already found throughout painting’s long history are cited and made available to be expanded, thus side stepping any formal or prescribed methodologies. The painting language is forged using a vocabulary that endeavours to reflect and explore present day concerns, both personal and aesthetic.

—David Rhodes

December 2014