Palaemon, A Survey of Paintings by Jon Imber

Curated by Elizabeth Hoy

Godwin-Ternbach Museum, Queens College, New York

June 2013

Below William Corbett celebrates Imber’s painterly freedom in an essay from the exhibition catalogue.

Jon Imber:

Younger Than That Now

By William Corbett

When I met Jon Imber over thirty-five years ago,the two modern American artists in his pantheon were Willem de Kooning and Philip Guston, his professor at Boston University. Jon’s painting life has been shaped by his response to the work of these two giants.

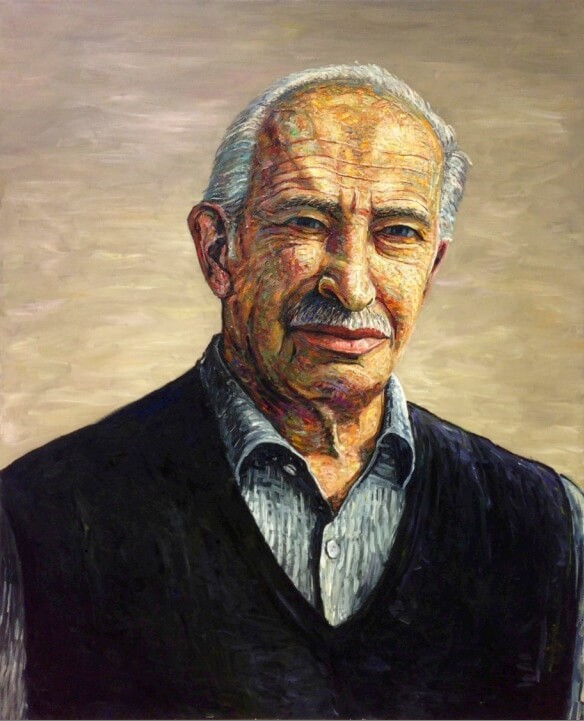

Jon’s paintings from the late 1970s through the 1980s took their inspiration from the monumental, sculptural qualities, the grounded weight of late Guston paintings. Jon worked from observation and memory to bring this force to real people, his parents and lovers, his distant relative Naftali Herz Imber (author of the Israeli national anthem, Hatikva), and with singular success to Guston. Jon’s portrait of Guston rises up the canvas; you must look up to him as you do to a hero, more in admiration and respect than in trembling awe. Jon’s Guston is a debt paid: a command, a salute, but a move forward—the lineage continues.

During those years Jon lived and worked on the first floor of a two-story square brick building off Somerville’s Davis Square. The basement of his building had been a screw factory and on the corner of Jon’s street stood Ray’s, a store that sold cigarettes, milk, and sneakers. I remember the studio as having no natural light. In that cave-like studio, Jon photographed Guston, myself, and my wife Beverly on Guston’s last visit to Boston in 1980.

Jon Imber is the one artist I know who married into his art. The freedom implicit in his landscape and flower paintings, brush stroke and image, begins to take hold in Maine, Jill’s home, and the home of Jon’s heart. He did not embrace this freedom at once. His paintings of hawsers, lobster buoys, anchor chains and boat gear now look like a farewell nod to Guston, late Guston in which the master piled natural forms—cherries in a nod to Chardin’s strawberries—and geometric shapes arranged with a startling muscular logic.

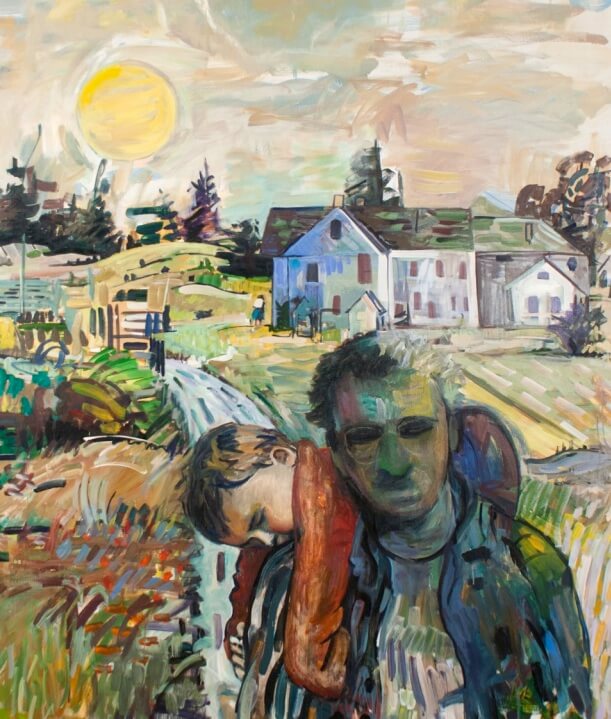

It is at this point that their son Gabriel enters his father’s paintings, asleep and carried, see Winter Self Portrait (1994) and Holding Gabriel (1994). There is a sequence of family portraits that settle into this new life and landscape, complete with the family dog Aretha. Jon begins to paint outdoors every Maine summer, and his other master, Willem de Kooning, liberates his brush. These paintings want the moment, an Eden of fresh air and light, bee hum, breeze stirred petals, and the parts of flowers that cannot be named yet Jon’s brush describes. He now works small to great effect and summons up the Maine landscape in horizontal paintings. His brush dances and darts, trails and drips, all wristy sweep. He swipes in blocks of light and brushy trees. Overall these paintings evoke a dream of now.

At some point Jon began to paint en plein air, upstate New York landscapes, the marsh and river around Concord’s Audubon Sanctuary, recording tangled undergrowth where he found it. I remember a tractor ploughing its furrow over a hill, silent country roads. At about the same time, he created small portraits, especially a knockout one of his painter-friend Helen Homer. I kick myself that I did not buy that picture or wheedle it out of Jon. Over the years I reviewed Jon’s shows as they came along at Nina Nielsen’s Newbury Street gallery. He liked it when I used the phrase “licks of paint” to describe his brushwork. I also remember a visit to Jon’s new Somerville studio. He was at work on a self-portrait, a mirror propped near his easel. “Sometimes I have to use it,” he shrugged, “because I forget what my nose looks like.”

In 1990 Jon’s life and art began to change course. The life-change happened when Jon married the painter Jill Hoy in the backyard of a friend’s home in Deer Isle, Maine. The art-change took place gradually and is still evolving. You can see the beginnings of this new course in the Boston University show curated by Katherine French, The World As Mirror: Paintings by Jon Imber 1978-1998.

Looking back I see Jon taking his first steps into a new world in “Escape From Deer Isle.” The naked figures resemble Picasso’s classical characters in their sensual roundedness, but the action and mood could derive from Maurice Sendak. This is a picture of lust, stealth, and sexy fears as woman chases man, the flowers of seduction thrust toward him by her outstretched arms. The painting quivers with delight and the risky turn-on of illicit freedom. You can’t say no even though you have no idea what you are escaping into.

At an opening one March night, Jon and I, together with and the Fogg Museum’s then curator Harry Cooper, talk about Jon’s paintings, surrounded by them on the staircase of Boston’s Psychoanalytic Institute. Although I cannot recall a word we said or any of the comments from the audience, it struck me as odd that the paintings presented were the most resistant to analysis. Their spirit is evoked in the words of Jon’s favorite poet, Bob Dylan: “But I was so much older/ then/ I’m younger than that now.”

As Guston and de Kooning walked out of Guston’s 1970 Marlborough Gallery show, Guston began to feel tremors of discontent. De Kooning too must have picked up the same vibes. He turned to Guston, and with a hand on his shoulder, said some encouraging words ending with, “It’s all about freedom.” De Kooning had put into words what Guston had felt—the freedom to do as he pleased no matter his surprise at the outcome. Jon Imber’s current paintings are born of a similar allegiance to the one standard every artist of quality must follow, freedom

—William Corbett