Peter Saul: Fake News

Mary Boone Gallery, New York

September 9 – October 28, 2017

Peter Saul once again transforms life’s lemons into delectable fare in “Fake News,” poking fun at faux journalism and his own excesses. Saul’s use of gratuitous violence surpasses the irony or humor of Disney or Wolverton, but pleasure follows alarm along circuitous pathways of gorgeous color.

The relatively demure “Blue Boy with Ice Cream Cone” quickly ridicules Gainsborough’s famous original. The assured contrapposto is an ungainly splay, and the noble gaze a goofy fixation. Drawing distortions look both careless and specific, unfolding in a dream-like way. Meanwhile, complementary color slowly acts out. A rosy-rust ground melts into orange, taut against electric blue attire that coolly recedes. The warm halo surrounds and flattens him, bending toward the oversized, dripping cone both overlapping and consumed by his form. Exacting hues prevent acidity, however garish color intention might seem.

Tonal emphasis and lack of surreal savagery in “Nightwatch II” makes things obvious; a militia of irascible Donald Ducks would be both risible and troubling. When Saul’s richly colored volumes are buoyed and abstracted through convoluted figure-ground relationships, however, his figures become almost metaphysical, like Magritte’s.

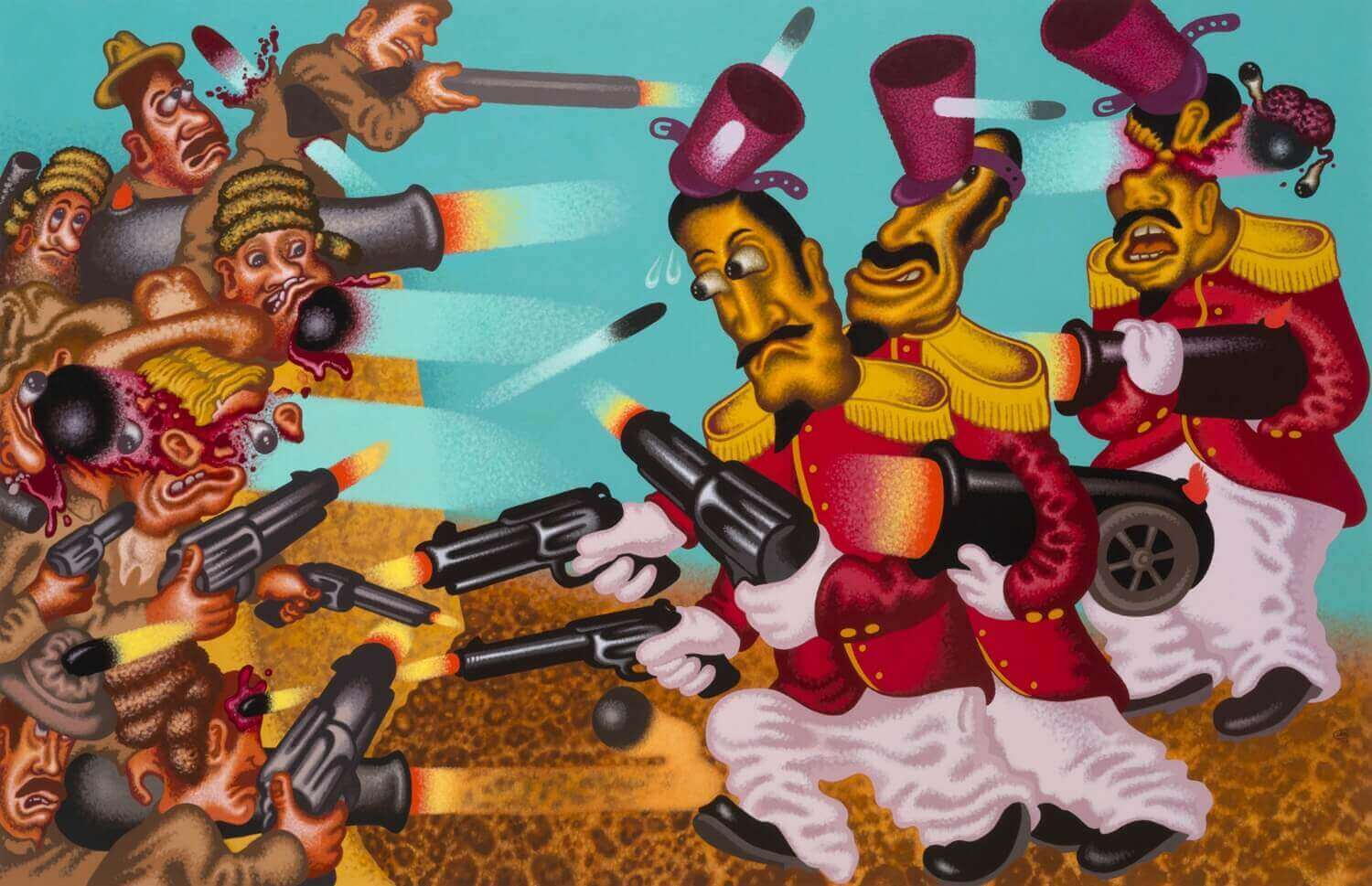

“Return to the Alamo” resembles Manet’s execution paintings, which were inspired by Goya’s, though Daumier seems a closer model. History painting’s complexity serves Saul well, but he’s not interested in oppositions of good and evil; despite exaggeration, his villains are at best banal. But facts enable farce, as they did Pee-wee’s meaningless adventure, which also toyed with the Alamo.

The Alamo story glorifies underdogs, the Texians and Tejanos vastly outnumbered by Mexican troops that ultimately defeated them. Yet in this scene contenders are nearly equal in number and weight. The few larger red uniformed Mexicans hold forth as they advance on the fort. One upper right fires a cannon as his own eyes, optic nerves still connected to his brain, fly like a putto from his bursting skull. The rifleman shooting him from upper left is blasted by a huge round from center, where his shooter’s bulging eyes lunge toward the bullet targeting him from lower left. That shooter in turn releases both barrels as his own head explodes, leaving his blond scalp smartly intact, facial features scattering like Mr. Potato Head parts. This slapstick, grotesque yet oddly soothing picture of mutually assured, instantaneous destruction seems to mock both warmongering and the average American taste for gore. The viewer’s eyes like heat-seeking missiles zigzag in satisfying rhythms of cause and effect. One may wonder if the artist notices the similarity of this visual volleying to EDMR trauma therapy, given his own childhood run-ins with Kafkaesque discipline. 1

Art is a great place to sublimate torments, as the history of Christian art shows – to transgress in truth-telling, or simply be passive aggressive in interesting and socially acceptable ways. Like other masters of these dynamics – Caravaggio, Dix, Clemente, Freud, Currin, Harkness – Saul’s formal expertise adorns his unvarnished stories enough that we open to them, while his thin, serene paint surfaces keep all emotion at a distance.

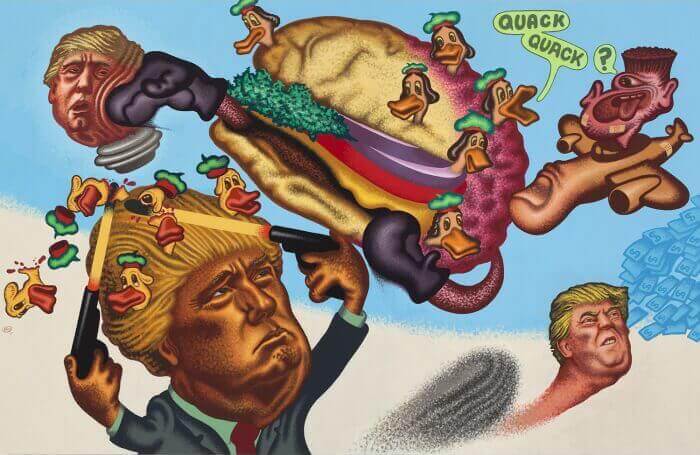

Saul’s characters, more obnoxious than sympathetic, are short on self-awareness. Driven by Id, they enthusiastically share their folly. So it’s no surprise he’s had a field day with the real caricature that is The Donald. “Quack-Quack, Trump” plays on “Duck Duck Goose,” a children’s game testing reflexes and competition. Here several Trumps vie with each other, as fragmented personalities do. One is about to drop an F-bomb near piles of blue money. The foreground spray-tanned one, solidly modelled, plays Russian roulette, shooting at tweet-like ducks growing from his scalp. A giant pugilistic cheeseburger turns into a brain, or vice versa, bullying another Trump. The bizarre flying thumb piloted by a flat-topped cyclops, straight from a bad dream, makes the Trumps more awfully real. Finely colored, droll forms render this monster-producing sleep of reason genial.

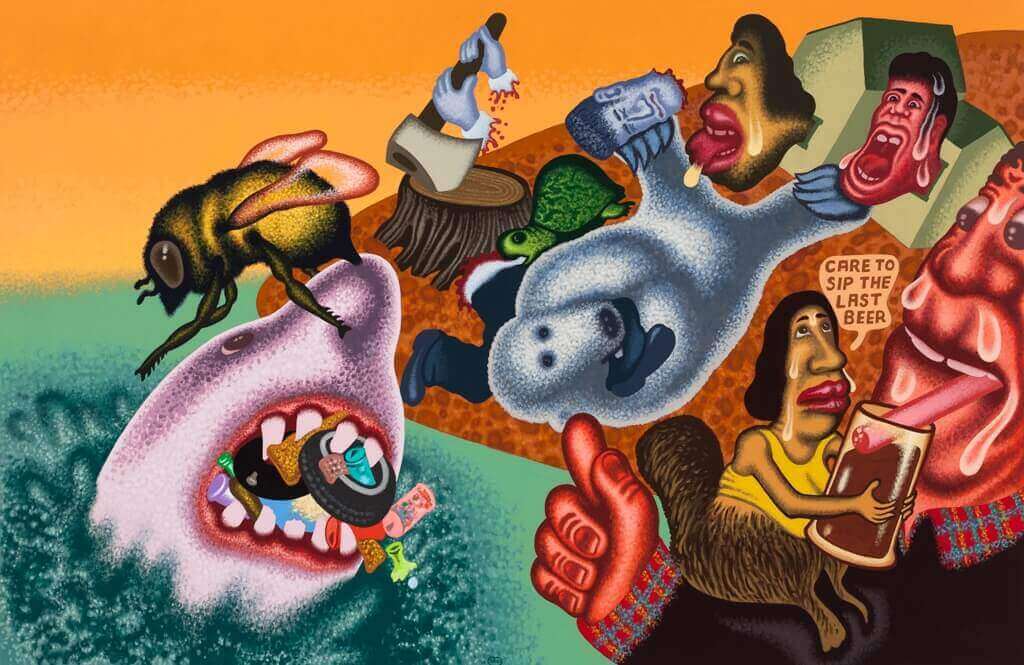

In “Global Warming, The Last Beer” an ominous hot sky launches a counter-clockwise tour through a hellish scene. A shark stung by a bee regurgitates ocean garbage; a polar bear devours he who apparently chopped down the last tree, his hands (reminiscent of Fra Angelico’s at San Marco) still clinging to the axe; and desperately sweating heads – one offered the planet’s final beer by a kindly squirrel-woman. Interweaving juicy colored, friendly shapes in gratifying spatial logic makes this dreadful narrative highly entertaining. Whether desecrating masterpieces or guiding our view with phrases too witless for poetry, Saul’s work articulates the chasm between the sense words can make, and the intricate visual reading his ambitious constructions require.

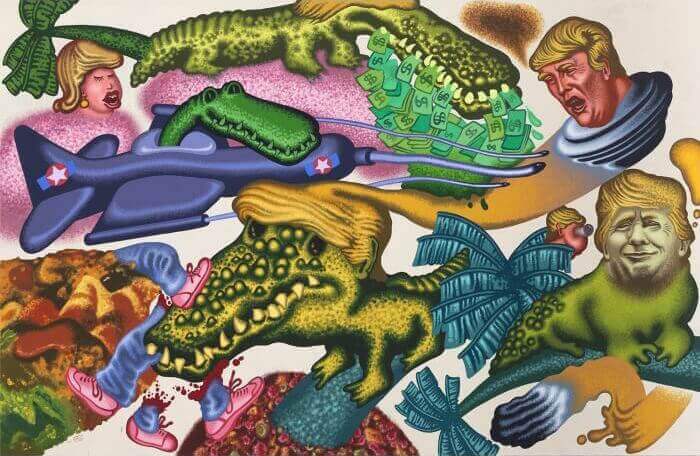

In “Donald Trump in Florida,” he is a cash-eating, a supercilious, and a carnivorous crocodile, and a disembodied, bloviating head like those in “Mars Attacks”. Warty skin and other revolting visceral textures fascinate, manipulated by temperature changes of the fairly saturated tropical palette. Rich greens ranging in intensity and value are more yellowish near purples and more bluish near oranges. As the loud, salmon-colored Trump head on a saucer turns back toward a charming purple, quiet fluctuations in the head below are savored later: Shadows are warm against his cooler greenish skin, but cooler against his hair. Like Matisse, Saul focuses ‘not on things but differences between them,’ equivocations that quell vulgarity.

In what amounts to a romantic defense of the art of painting, as well as epic satire, Saul powerfully activates the realm between the nameless and named – the former including the “millions of colors” computer monitors describe, the latter the many ways Trump symbolizes humanity’s dark side. Saul has met the enemy and it’s us, and imparts this discomfort beautifully.

Notes

1 Robert Storr, Peter Saul: A Retrospective, 2008, p. 38.