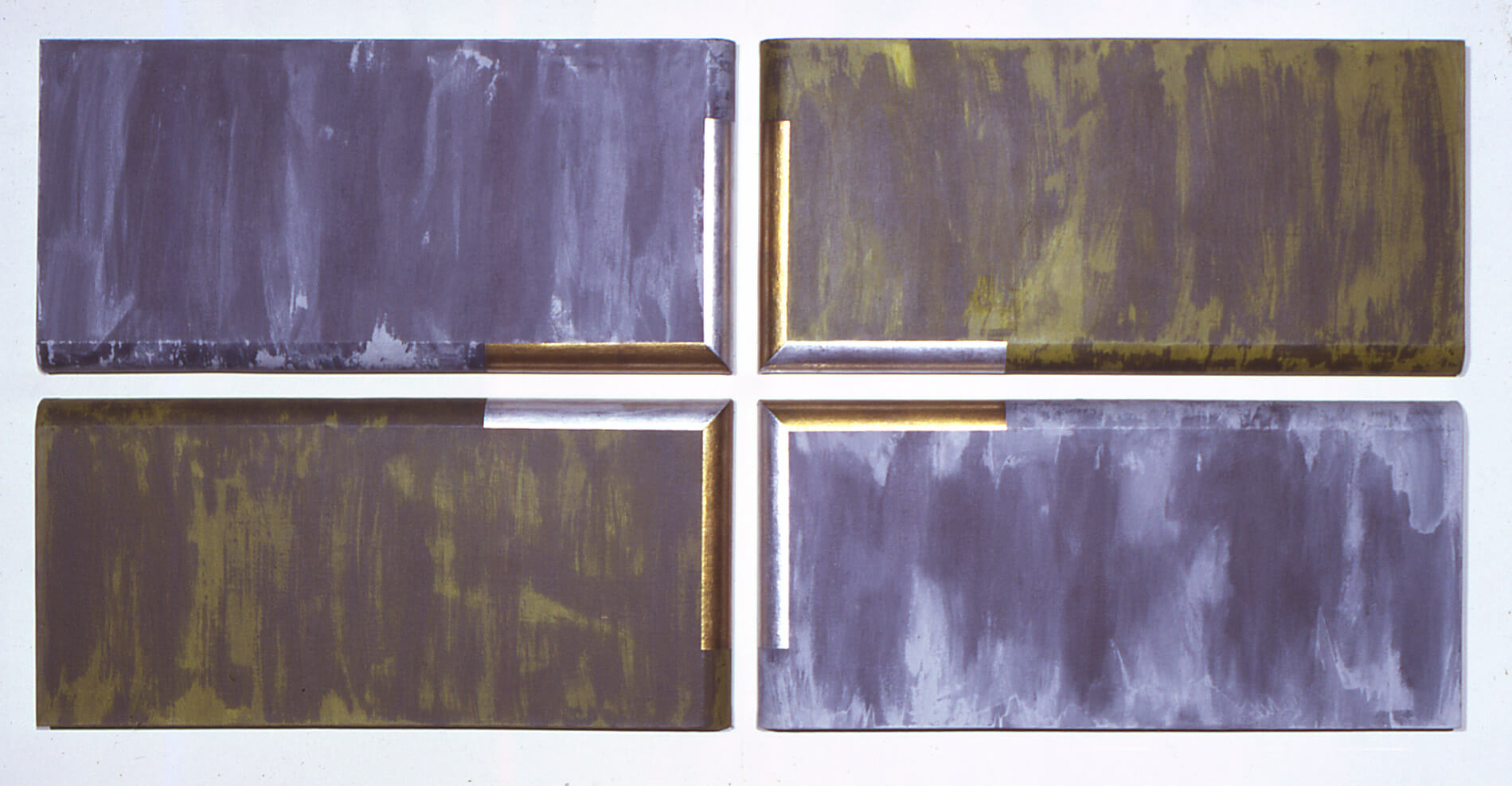

Editor’s Note: Thank you to Dana Gordon for providing this remembrance of two great artists – George Sugarman and Tony Smith. Reading Gordon’s account, it is also interesting to see the visual conversation the young painter had with these two sculptors. The echoes of that dialogue are also evident in Gordon’s most recent paintings which will be on view at Andre Zarre Gallery, New York from November 11 – December 6, 2014 (Reception, November 13, 6-8 pm).

—Brett Baker

I worked for Tony Smith as his studio assistant for about a year and a half in 1968-69. I also worked for the sculptor George Sugarman, for a few months in 1967. I met Tony and George when I went to graduate school in art at Hunter College.

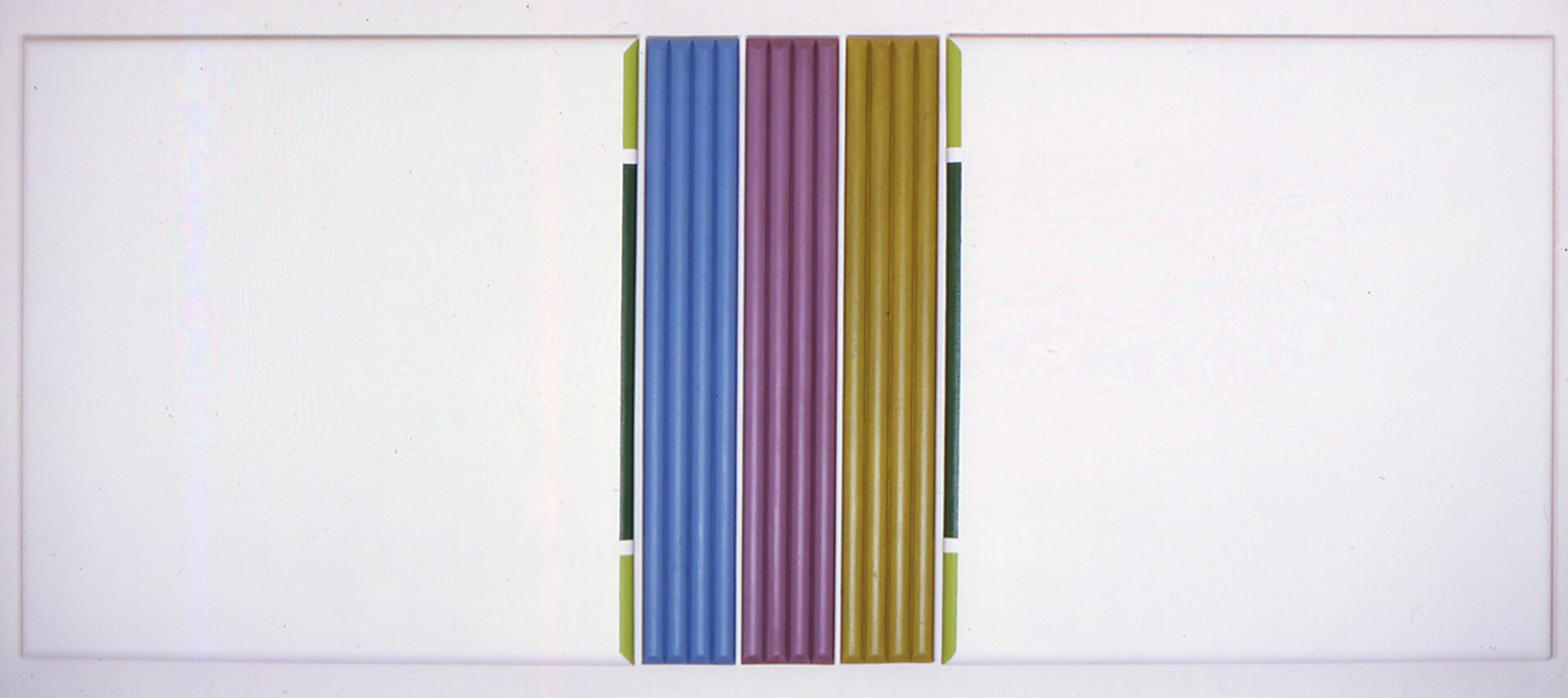

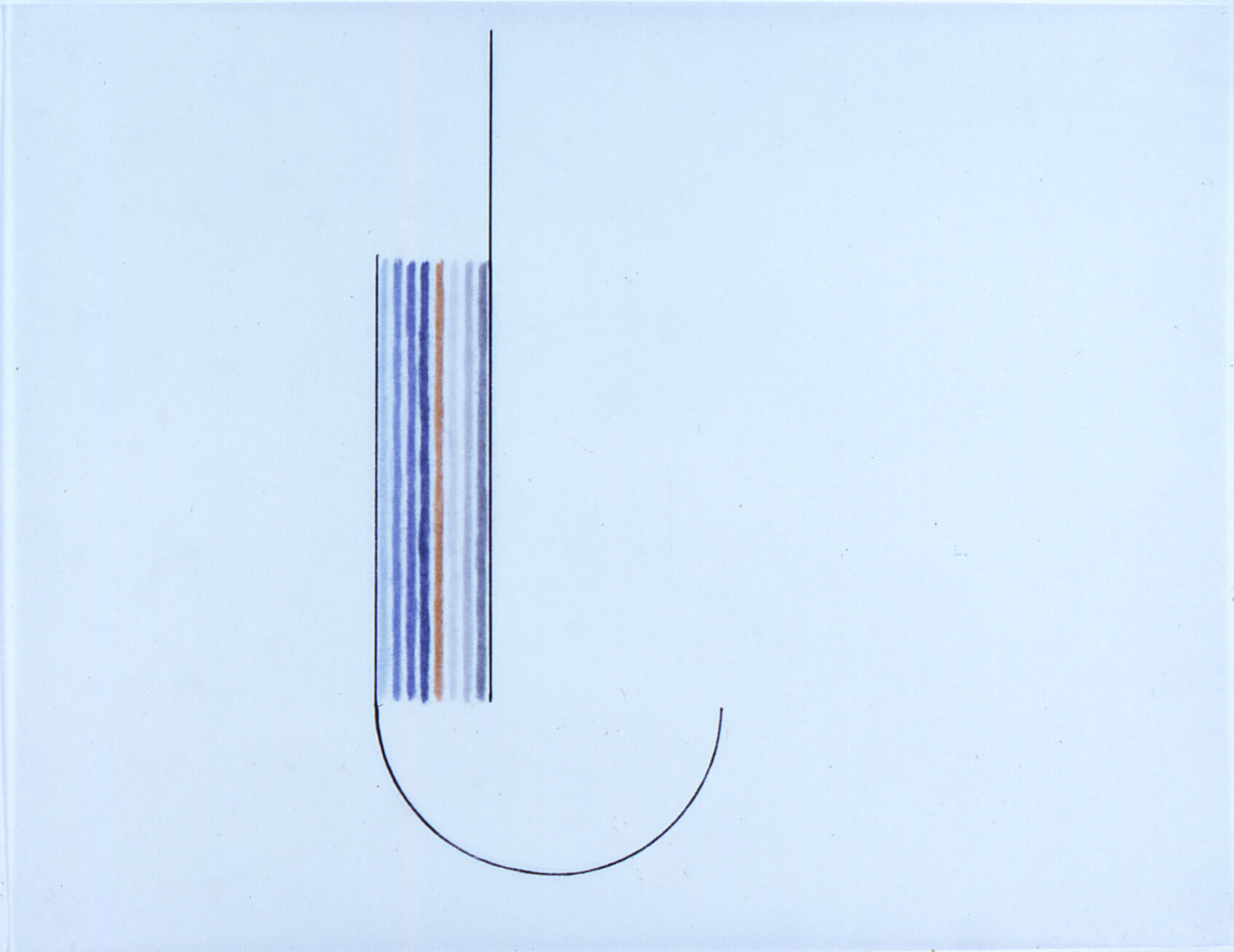

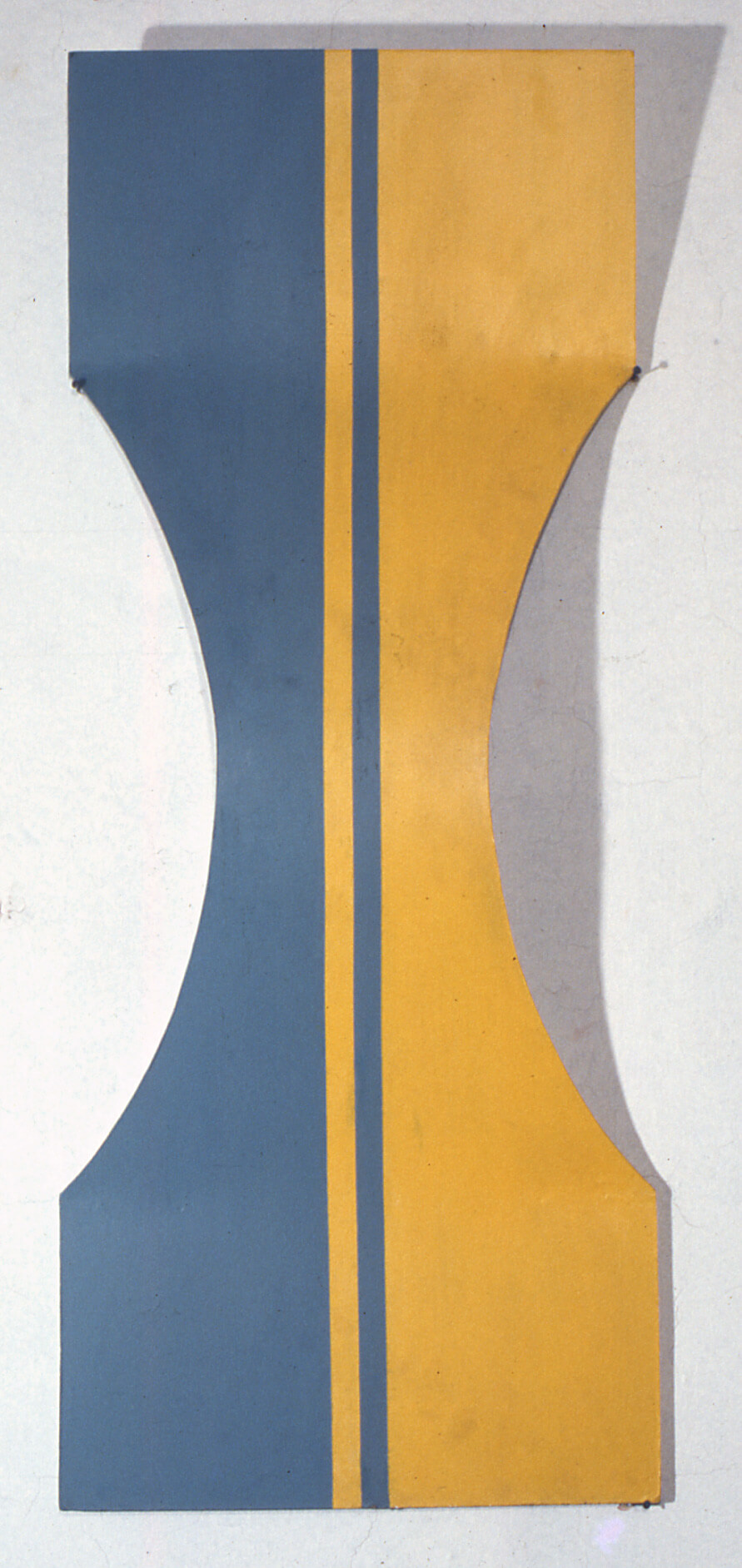

Though I was a painter then as now, I was very interested in George Sugarman’s use of color in three dimensions, in sculpture. I was making paintings in three-dimensions. The main thing I remember from him as a teacher is that he emphasized that your artwork is the answer to the question you pose in embarking on it, “what is art”. This stayed with me for quite a while.

George liked some drawings of mine, of odd colored shapes in a row. They looked like some sculpture he had done. He also told me, when I was looking for a studio, that Brice Marden was moving out of his studio on Cherry Street. But Marden wanted too much key money (I had none).

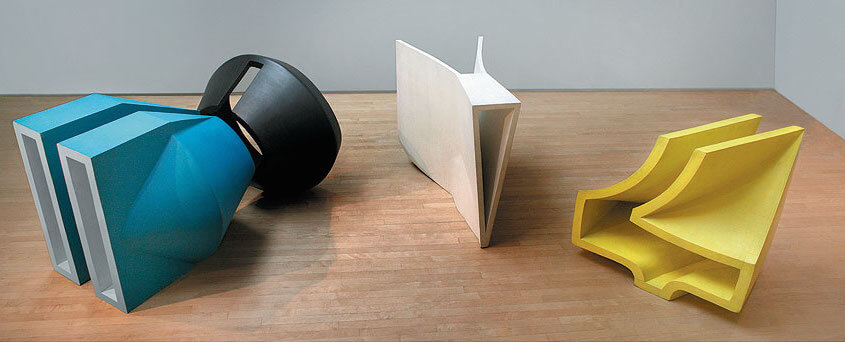

Working for George was hard. His big rounded forms were made by laminating many layers of thick lumber into bulky crude shapes and then cutting away at them. Immense clamps and tubs of white glue were omnipresent. I spent the day using power tools to carve and sand huge slabs of glued-together sugar pine board. I developed a lifelong aversion to sawdust.

The pieces would become more finely formed and sanded but showing the lines of the glued-together wood, then these would be covered in white primer paint. When a piece was nearly finished, a big swath of colored shape on one curved plane or more would appear in the loft space.

His studio was on Greene Street just below Houston. In those days, before it was called Soho, the neighborhood’s streets were clogged with belching, loading and unloading trucks. The lofts themselves would fill with air pollution, if you left the windows open during a weekday. George had a big empty loft. Twenty feet wide, half a block deep, very high ceilings, windows at both ends. Classic. Worn wood flooring running parallel to the length of the loft, emphasizing its length. George had it sanded light and shined it. The two long uninterrupted walls were a sooty white; maybe with a little tinge of blue.

Nothing hung on the walls. Two or three large sculptural forms, easily seven feet tall, in progress, sat poised about equidistant along the middle of the room.

There was something zen-like about the way the environment was so completely given over to one thing, making and looking at his sculpture. There was nothing but these forms in the big loft space. Tools were not left lying around. Indeed they were wrapped up carefully in their cords, shipshape, just like in the Navy, in which George had spent WWII.

In the back of the loft against the windows there was a tight space used for something akin to living, or maybe just relaxing. A rumpled bed, easy chairs, a wooden table, some items jammed into shelving, a curtain hiding some other things. The windows were old and dirty, but light came in them, as they weren’t blocked by another building.

There were few visitors when I was there; mainly the critic Amy Goldin came by once in a while.

George could be voluble, but taciturn as well, switching on and off. He liked to refer to his friend Ronnie Bladen quite often. He told me of his friend David Weinrib, a New York artist who hated to leave town. When Weinrib finally did acquiesce to a respite in the country, once he got there he couldn’t stand it after a few hours and went right back to the city.

George struck me a bit as a tough but sensitive working class type of guy – with brilliant insights about sculptural form, which he deeply understood – and I had the feeling that he was something of an eccentric loner. He wanted his work to be beautiful as well as intelligent and deep. He pronounced the word “byoodee-ful”, not beautiful.

George Sugarman’s sculpture was a pretty big deal in the 1960s and 70s. Its highly visual development goes deep into the abstract possibilities of sculptural expression in unique and important ways, in a search for pure and complex expression in abstract form.

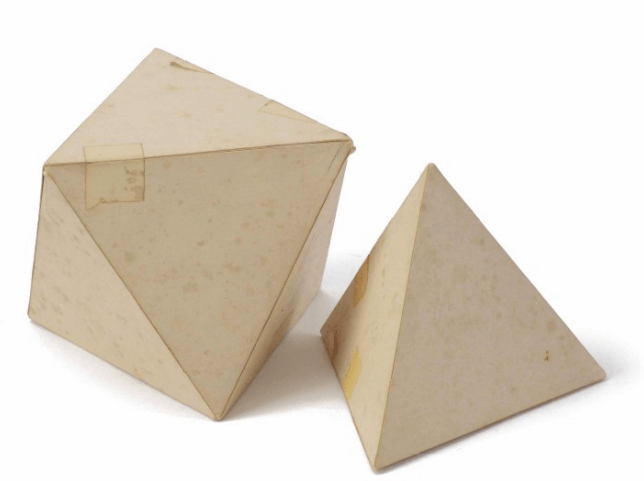

Working for Tony Smith was a different experience entirely. I made drawings – sketches and mechanical working drawings – and cardboard models for his pieces. Sometimes he would just tell me about a piece he had in mind, just orally describe it, and I would draw it. Other times I had to make dozens of little three-dimensional cardboard modules, tetrahedra and octahedra. He would tape these together into unpredictable shapes that you never would think are made up exclusively of (what I call) abstract expressionist drawing in a tetrahedral/octahedral space lattice. Then I would make models of these in careful scale to send to industrial fabricators.

Tony also paid me twice as much as George did, $5 an hour instead of $2.50.

To get to Tony’s I didn’t walk from the East Village to Soho. Tony lived in the Oranges in New Jersey then. I could take the Hudson Tubes, i.e., a PATH train, either to Newark or to Hoboken. If I took it to Newark, Tony’s wife Jane would pick me up. If I went to Hoboken, I took a clickety clack train from the old Erie Lackawanna terminal out to Mountain Station. Then a longish walk up a steep wooded suburban hill.

We worked in one of his two houses in the old settled, leafy suburbs. Though not far apart, the two houses were in two different towns and I could never remember whether they were East, South, or West Orange.

Tony lived and worked in a huge red-brick Georgian mansion that he had recently bought with a down payment his friend Barnett Newman had given him. The house had big beautiful front and back yards, dark green lawns with old trees – a towering old spreading, yard-filling beech tree he particularly loved, and squirrels he hated. The house itself was nearly empty of furniture. His daughters, the elder Kiki and the younger twins Annie (Seton) and Bebe, lived in another house nearby – the beautiful old shingle-style house Tony himself had grown up in. His devoted wife Jane was a presence in both houses. Despite the old suburban location, both houses had a bohemian tinge. Inside the shingle style house, the walls showed years of unrenovated wear. And in the Georgian, the sparse furnishings were basically limited to a huge, treasured grand piano of Jane’s, an elegant ebony dining set, a large drafting table in the basement, and a bit of necessary bedroom furniture upstairs. Plus a few artworks. No frills or froufrou. There was a big garage in the back, in red brick to match the house. It was filled with a pile of big black-painted pieces of plywood, the disassembled sides of full scale mock-ups of his sculpture. Also piles of things, like used milk cartons or egg crates – everyday containers he re-purposed as modular forms for building sculpture ideas. At this time, in the house and out, there were only a few, literally two or three or four, pieces of completed Tony Smith sculpture, of different scales, mostly small.

Tony liked to tell the story of how he got the house. When it was for sale, it was still full of the old long-time owner’s furniture. The furniture and decoration were old fashioned, to go with the Georgian architecture, expensive and elaborate, and filled every room. It was so impressive, that no one thought they could afford the house, so the price came down, and Tony got it.

Physically, Tony looked robust, with grey and white curly hair, and searching eyes that were inset and a little bulging at the same time, magnified by his glasses. His white/pink skin could be florid or pallid, sometimes both. He was a proud Irishman, and soft spoken and gentle of approach. He spoke with a delicately demonstrative turn of the wrist and palm this way or that. He was dogged by illnesses then. And illness had been a characteristic of his childhood: part of his lore was an oft-told the story of having TB as a child and being quarantined to a small cabin in the backyard – of the very house his family lived in now. Yet illness was not part of his persona that I could see; he was a bright character.

Jane Smith was patrician – tall and slim and had the most cultured voice and manner imaginable. Both Tony and Jane were extremely genteel, kind, and personable. Before having a family with Tony, Jane was known as Jane Lawrence, an operatic singer and actress, which explained the presence of the grand piano in the mansion, and the occasional reference to their friend, Tennessee.

When I arrived in the morning Jane would immediately offer me breakfast. It was so politely and perfectly offered, I felt like I would be an ingrate and an oaf if I refused it.

Tony slept late and I often had to wait for his instructions before working. So I sat with my breakfast and waited. Part of my job was to sit and chat with him while he had a little breakfast (perhaps it was a vodka) after he woke up and came downstairs and before he was ready to get to work or greet visitors. I was often ill at ease during these passages of time because I didn’t think I could say much of interest to him. Still, he liked to talk to me and he sensed that I understood him, which I thought I did.

Smith was very generous. He was known to help his friends whenever he could. This included job recommendations – for the always precious college teaching job artists usually needed. He had old friends and admirers on faculties all over the place. Once he recommended me to his friend Peter Fingesten to teach drawing at Pace College. Another time a couple of years later, I received a letter out of the blue offering me a job in the art department at Michigan in Ann Arbor. Though no one ever told me of the connection, I found out that two old friends of Tony’s from New York in the 40s and 50s, Gerry Kamrowski and Bob Iglehart, were on the studio faculty there.

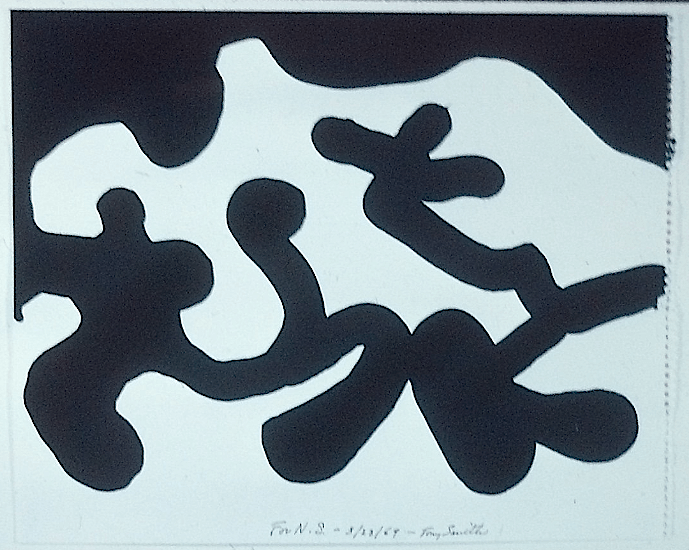

Generous though he was, he told me in no uncertain terms, never give away your art. And yet, in the years I worked for him he gave a friend of mine an old wood sculpture that had been rotting in the yard of the old house, and a drawing. The latter he drew as we watched and then he gave it to her. I guess the rules were different for flirting.

Mostly, his big newly acquired house where we worked was empty and quiet. But occasionally an important visitor made his way out there. I recall meeting Sam Wagstaff, the curator and major patron who (avant Mapplethorpe) gave Smith’s career a big boost. Donald Droll, Tony’s New York-based dealer came out more than once. And someone in elegant European tailoring came about a commission from the Banque Lambert for its famous collection; perhaps it was the Baron Lambert himself, or his curator Pierre Apraxine.

Tony’s good friends included Mark Rothko. One day I was detailed to take Tony’s car, a new white Volvo station wagon, and bring Mark Rothko out from the city for dinner, to which I was invited as well. I picked Rothko up at his studio. This was a cavernous, exquisite old carriage house, on East 69th Street between Lexington and Third. I arrived in early evening. It was already dark out. The door was opened by his assistant, Oliver Steindecker, the same unlucky fellow who two years later found Rothko’s lifeless, suicided body in the bathtub of this house. At the time I picked him up, Rothko was working on very large paintings, easily accommodated by the cathedral-like space of the carriage house; indeed, the paintings were almost dwarfed by the space. The space was dimly lit, though I don’t know if this is the way he worked. As I recall, the space was hexagonal or octagonal, possibly square (like a cube), definitely not rectangular. It’s back in hazy mythical time for me. It felt something like an ancient Byzantine church. The interior walls were a shiny light beige brick. I drove Mark, his wife Mell, and their young son, whom they called ‘Topher, along with a friend of mine out to New Jersey.

Also joining us for dinner was Theodoros Stamos, Stemi, as they called him. Stamos was a famous ab-ex painter in the 1950s, his reputation somewhat fading in the late 1960s. A little later, he was one of the executors of Rothko’s estate and was, along with the Marlborough Gallery (a hugely influential gallery in those days, which showed Stamos) and others, implicated in defrauding the estate in a massive scandal that colored the artworld in the 1970s. But in 1968-69 they were all friends.

So we sat down to dinner, me and my friend, Tony and Jane, Mark and Mell and Topher, and thickly-mustachioed Stamos. Across from me on the wall behind the table hung a sizable, beautiful bluish-grey gauzy painting by Jackson Pollock, another close friend of Tony’s, then but a dozen years gone. A dozen years past was a long time for me then, but probably not for Tony. I felt the ghost of Jackson Pollock hovering in the dining room; maybe Tony did too.

Jane hosted the elegant, simple, precise dinner; there was no help or staff. Alas, I do not remember any of the conversation. Maybe it wasn’t memorable. As a 24-year old new artist sitting among the gods, I found it difficult to contribute to the conversation, though I was included in it – they didn’t comport themselves as gods. And Rothko, sad to say, was already, and clearly, a black hole of depression, emanating a pall from where he sat.

Around 1980 a book was published that gave a detailed account of the sordid fraud and trial of the Rothko scandal, “The Legacy of Mark Rothko,” by Lee Seldes, which I read avidly as soon as I could get my hands on it. In the early 1980s, I was showing my paintings at the Ericson Gallery, owned and run by Takis Efstathiou. Takis occasionally showed work by his fellow Greek, Stamos. Early one evening I walked in, and sitting there was Stamos, unmistakeably weighed by the heavy aura of the very villain and fool, in the dark story limned by Seldes. It was eerie. Yet another early evening not long after, I walked in and sitting their was Rothko’s last assistant, Oliver Steindecker, the one I met when I picked up the Rothkos for dinner, the one who found Mark’s body. Very eerie.

A couple of years after my dinner with Rothko, I was working at the Honolulu Museum of Art. Tony came out to work on a piece he was commissioned to do at the University of Hawaii. We spent a day together. Tony was a vodka alcoholic, the kind who could drink it all day long and remain apparently lucid. It was quite amazing. I drove him around the island from 11 AM to 10 PM, showing him the beautiful and unusual forms of land, flora, and water. During this time he consumed eleven double vodka and tonics. There was little change in his demeanor. I sipped drinks along with him, to be polite and to be at least a little on the same plane of perception. But of course I had to drive. And I didn’t have anywhere near the same capacity for alcohol.

Smith had the reputation of something like an Irish bard. He liked to recite parts of Finnegan’s Wake from memory. He was an avid storyteller, especially stories that had to do with art. Some became almost legendary, like his famous story about driving on the unfinished New Jersey turnpike at night and seeing the two massive, endless, gently curving, raised strips of pavement as a wholly new kind of aesthetic experience, a new kind of art. Interestingly, he didn’t try to imitate this specifically in his art; but he wanted to create the kind of experience he had there. And he combined it with insights from his other life experiences of workings in three dimensions: e.g., he had worked as clerk of the works for Frank Lloyd Wright. He was an enthusiast of Buckminster Fuller; he had studied with Moholy Nagy at the New Bauhaus in Chicago. His father ran a foundry that made the hydrants for much of New York City. But painting was a big influence on his work, too, via the abstract expressionist painters who were his friends.

Tony had hired me because I could draw the pieces he would describe or sketch. He also liked that I had some experience in common with him, though I had come by it maybe 20 or 30 years later. I came to know and love Frank Lloyd Wright’s architecture, while I grew up near it in Chicago, and I thought of studying at Taliesin. I knew Fuller’s work and ideas, which were very hip in the 1960s. And I had spent a year in graduate school at what had started out as the New Bauhaus, the Institute of Design (ID). The school’s building was a great monument of modern architecture designed by Mies van der Rohe. At ID I studied photography with Aaron Siskind, who Tony knew from the New York art world 20 years before, and with Arthur Siegel, whose every second or third sentence was Moholy this or Moholy that.

On occasion Tony spoke about Pollock, whose work and life – though he was already in art Valhalla – wasn’t as thoroughly over-examined then as it is now. Tony colorfully described times he spent with Pollock, whom he always referred to as Jackson. They got plastered together and Pollock then painted. And Tony made comments about the paintings as they developed. At least, these were the stories, which I saw no reason to disbelieve.

Geometry can be found underlying all, or nearly all, the forms in nature. One learns this from D’Arcy Thompson’s book “On Growth and Form,” a favorite of Tony’s, and from Jay Hambidge’s “Elements of Dynamic Symmetry,” another favorite of his. You can learn this just from observation, if you look intently enough. No form in nature is a perfect example of the geometry it is a case of, but when you average the many examples of one form – many examples of the skeletal structure of a bird’s wing, or the arrangements of leaves on a stem, or cellular or atomic forms – you get the perfection we normally ascribe to man-made geometry. And all man-made geometry is natural, because we are nature.

Looking at things this way, there really is no difference in kind between geometric and biomorphic form.

Tony Smith’s artistic expression was based in something like this perception. He decided to represent our given “amorphous” space that we live in (the blank canvas, the empty space that precedes a sculpture) as a three dimensional space grid or lattice. For his sculpture, the type of lattice was sometimes made up of right angles, but usually was the more complex and productive tetrahedral-octahedral space grid, based in equilateral, 60-degree triangles, and forms that logically cutting these could generate. He would imagine as if this lattice defined or contained all possible form and movement in the space. Form could only follow the lines and angles of it. But within this constraint, he drew freely. Like an abstract expressionist – but keeping to the rules of the grid space. Thus his forms are unpredictable, but all can be seen as precisely sitting in the chosen grid, with no part not fitting. In most of the sculptures this is not obvious, but it is there.

The space grid or net appears in art, and in life, in many ways. Maybe more obviously in the digital and Internet age than before. It is usually full of impure parts, curves, and lack of true repetition, until it gets improved for some use or other. In art, the netting in Pollock’s painting that results from the palimpsest of free drawing is a good example. I suspect Smith combined his intimacy with Pollock’s process with his own passion for architectonic form.