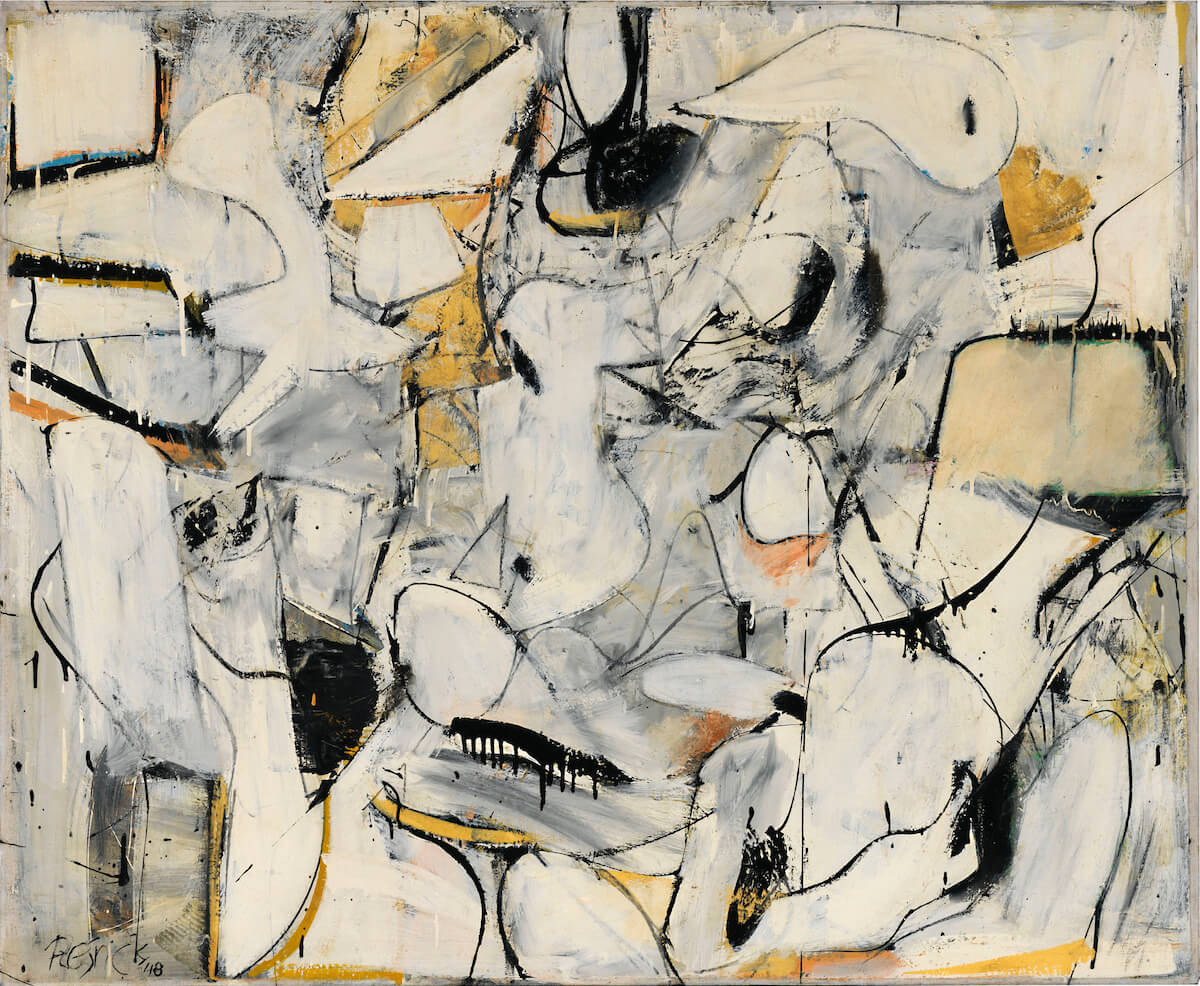

Milton Resnick (1917-2004):

Paintings and Works on Paper from the Milton Resnick and Pat Passlof Foundation

Mana Contemporary, Jersey City, New Jersey

May 10 – August 1, 2014

On the occasion of the exhibition Geoffrey Dorfman, painter, author of the book Out of The Picture: Milton Resnick and the New York School (Midmarch Arts Press), and Trustee of the Milton Resnick and Pat Passlof Foundation, generously agreed to discuss Resnick’s life and work with Painters’ Table.

Painters’ Table (PT): There hasn’t been a major retrospective of Resnick’s work since the one in Houston in 1985, a show which pre-dated his later, more figurative work. In curating this exhibition, what was the most surprising thing about juxtaposing works from all phases of his career?

Geoffrey Dorfman (GD): I’ve known both Resnick and his work since 1972 so nothing was likely to take me completely by surprise. On the deepest possible level certain things reoccur over the decades that, small as they seem, hold significance. For instance, at the Foundation I’ve found two small works made a half century apart that both feature several primitive marks – no corners or twists — which somehow freeze the surrounding field in an uncanny way, as if the painting were holding its breath. This idea of a something transitory, momentarily held in suspension — arrested — is something that was important to him. He’d talk about flinging playing cards into the sky and having them stick. He suggested it to David Smith, who was also showing with him at Howard Wise Gallery, as an idea for a sculpture. Even in Milton’s late Genesis paintings, the snake is often pasted in the sky.

Resnick was a poet, so he could make this idea vivid in words:

Like straws the wind obeys your feelings.

It also has resolution.

It collects all that passes for nature and waits.

That hesitation makes your eyes shine.

Then it blows away.

Milton was not alone with these thoughts. You see others with similar ideas. For instance William Gass in his, ‘On Reading Rilke’ writes,

…a stone set in motion or a motion held like a pose: that every accident should be made necessary, and every necessity look like a towel thrown over the back of a chair.”

It reflects a certain aspect of Modernist sensibility that is not understood too well, but it’s one thing to be aware of it and entirely another to be able to achieve it. Anyway, it serves as a touchstone throughout Milton’s career. It’s at the root of his aesthetic.

PT: Although Resnick is best known for his large abstract paintings, there’s a great variety of imagery throughout his late work: couples, the serpent, the tree, grave stones, windows etc. How does Resnick’s late iconography connect to his earlier work? Does his introduction of imagery late in his career deepen or alter the reading/experience of the earlier work?

GD: Resnick called figuration, “beating a dead horse,” and he was openly derisive about it. So it was surprising when he took it up, himself. But in my book, “Out Of the Picture,” we talk about that, “You always come around to what you hate.” In other words, you try the opposite tack. In the late 1960’s he told the kids at the Studio School to cut off all their hair, just to find out what it would feel like to be painfully exposed; to de-culturate themselves. Milton himself experimented with how he would appear to people: crew cut serviceman, poet-maudit, convict, Jazzman, prospector, magus: by the time he died he looked pretty rabbinical, like Pissarro’s twin brother.

So although Milton had very strong beliefs, he was not a typical ideologue. He would assume the contrary, just to test himself. I’m sort of avoiding your question: I’m cautious about answering it simplistically. The figuration of the 1990’s wasn’t by any means a rejection of his earlier paintings. Nor was it a return to something earlier. He was always abstract, unless you go back to his student years in the 1930’s. Yet any time you start to have shapes in a picture, there is ‘implication’ present. People can read into just about any shape; their imagination is fertile. You’re not avoiding that by embracing geometry either. Recognizing a stripe or grid is functionally the same as recognizing a waterfall, a crucifix, or a pile of laundry. ‘Meaning’ is a refuge from the sort of confrontation a painting ideally ought to provide. Why? Because the belief that one understands —can identify — what one is looking at, ineluctably domesticates feeling. It leaves the audience feeling comfortable, and that’s not the artist’s business. Museums feel that if they don’t tell the public what it is they see, they won’t come. So they’re in the acculturation business. Art is actually something else entirely.

By 1985 he was exhausted, physically and emotionally. He felt that he was able to take “the blank” to where he couldn’t go further. He was getting old, experiencing a lot of pain, but he wasn’t dead yet. What to do with the time left to him? Painters don’t retire, you know. So he got a hold of some used Victoria Secret catalogs, cut out images and painted from them; then he re-interpreted Rubens, Poussin, Renoir and what-not, and finally hired models to sit for him. That’s how it got started, and with that, the themes of Genesis and the Judgement of Paris, which he lifted from Classical art and integrated into his overall aesthetic vision. By doing so he found himself back in the world of composition. This was inevitable because Milton embraced the tyranny of the rectangle. He thought it an a priori condition of painting, as he understood it; sort of like having foul lines on a field of play; without them you don’t have a game at all. Or if you do, it’s another game pretending to be yours. He didn’t talk about it, but he didn’t have to. It was very evident. But all the other conventions of figuration: gravity, volume, room, near and far, light and dark; they don’t enter into it except as epiphenomenon, the flotsam and jetsam cast off from his paint handling. The man and the tree are just versions of the same thing, a ‘Y” shape or a cruciform. Later, they become crosses an X’s. The paint itself was supposed to be the vehicle of feeling; not the iconography. The latter was just a way to keep going, ie. to put gas in the tank. Resnick may have lived to paint, but towards the end he painted to live.

PT: The New York School painters were a particularly diverse group of artists which is remarkable given that they lived and worked in a much smaller, closer community than is imaginable today. A number of formidable and unique sensibilities emerged from this community – Resnick among them. Where does his work fit in the story of Abstract Expressionism?

GD: For Resnick, AE dovetailed with the rebirth of his life as an artist. In 1945 he was busy resuming painting, acquiring a studio. His work from the 1930’s had been entrusted to his friend, de Kooning for safekeeping, but over the intervening five years of his military service, Bill lost it. Milton was therefore starting anew. He looked at what Bill was doing and picked it up immediately and ran with it. There’s a Resnick painting at the Metropolitan Museum from 1945 that precedes de Kooning’s Judgement Day. It’s not as resolved as the latter but you can see Milton had ‘acquired’ it in advance. Yet, in truth he had barely taken off his uniform. A few months later they collaborated and blew up Judgement Day to serve as the backdrop of a dance performance; I think they painted it overnight. Bill scaled up his composition, mixed the pigments and Milton painted it. That was Labyrinth, right at the start. When the Abstract Expressionist period ended about 17 years later, (which is to say when the public’s attention was directed elsewhere,) Milton was only forty five years old. Motherwell was forty six; Reinhardt, forty-nine. Pollock, (were he alive in ‘62,) would only have been fifty; Kline fifty-two. None of them old men. Several of these men died in that period, and most of the rest not long after, but Milton painted until 2004. So Abstract Expressionism began the journey. And of all of them, I would say that he took it further, cultivated that ethos over decades, a vision of art that he bought into completely, and developed and enriched by placing increasing demands upon himself. Paintings like New Bride at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, or Saturn at the National Gallery in Ottawa, or Elephant, which we have at the Foundation and is now on display at Mana Contemporary, are landmarks of abstract art of the last century. The Whitney also has a superb vintage Resnick to go with the much earlier Lowgate, (1957) and Genie, (1959.) The fact that these institutions don’t show this art, and are sort of oblivious to what they’ve got, is unfortunate but changes nothing.

When attention shifted to artists like Warhol and Lichtenstein, many of Resnick’s associates wrung their hands. Rothko was, for one, nearly apoplectic. All the attention was creating a mad dash towards manufactured originality and notoriety; in other words, public relations. Milton basically took the attitude that he could accomplish more with the spotlight turned away. I would opine that’s the only position to take and keep your sanity. And he was proved right. The proof is in the pudding, as they say.

PT: Resnick’s best paintings (for me the Elephants and other paintings of that era) seem to separate themselves from the intentions of the painter. They are painting personified; they become autonomous, awesome, even terrible beings. In the presence of those paintings I’ve experienced what I can only call “looming” – the feeling that a powerful, bodily life-force is encroaching on my space. They literally backed me up. These works are not pictures, they’re Paintings, and Resnick is their creator – he gives them life and sets them free.

GD: I’ve got to agree with you. They are not personal paintings except tangentially so; they’re personal only in the sense that they are produced by an individual consciousness. If you and I try to paint the same thing, it will nevertheless look different. That’s the nature of art, and we prefer that it be so. That’s much more interesting than people deliberately trying to be different. That gets old real quick. Anyway, Milton aimed for the universal, not the personal. He was very clear about this. One of his best lines — he spun it out in a debate without thinking — was, “You’re not very original if you want to be an individual.” He’s right; it’s the most commonplace idea imaginable. So your intuition is correct, I think. In the great Resnicks, there is a spell cast, a presence but not a personality; something more stand-offish; inexorable but impartial. The fact that many of those paintings are dark doesn’t hurt, but that sense of the sublime is also present in New Bride, 1962, which is nearly white. You know, I’ve just reminded myself that Melville has a whole chapter on the color white in Moby Dick. White for him was the color of death. But Milton had no dread of death. World War II cured him of that. When you see so much of it, it just becomes another moment.

The other aspect of it is that it is that oblivion — the sense of the blank — can be very powerful. The paint remains paint; it doesn’t look like anything but itself. It resists the word. It doesn’t describe, but it also resists its own description. It’s meant to do that. That it can evoke these somewhat mystical feelings in susceptible people is hard to account for. And let’s face it; it’s not for everyone. An executive of Pace Gallery called it shit on a shingle, but his idea of a great artist is Eric Fischl. It takes all kinds to make a world.

There have been many ‘blank’ painters over the years. There still are. I could name names. Nobody I know of though, creates these sensations. For example, when Color Field painting becomes materials and techniques, it diminishes your experience. You find yourself in the kitchen with those artists. With Resnick there is no technique. There is no apparatus; there’s no squeegees, no airguns, no additives or gels. Nor is there any virtuoso element to speak of. It is actually close to nothing. But at the same time it so obviously isn’t.

PT: The more one looks at Resnick’s paintings, the more unique his body of work seems – yet no art is conceived of in a vacuum. What is Resnick’s artistic lineage?

GD: First I should mention the artists Resnick talked about; Soutine and Cézanne. Referred to those two more than other artists. Monet did not excite him nearly as much, although he thought him a very great artist. There would be more talk of Rubens and Delacroix than Monet. Milton thought Rubens more important than Rembrandt. Milton favored those turbulent interlocking forms of Rubens that prefigure the abstract art that interested him, and he talked of Ruben’s high space — aspirational space — which I took to mean the sense of ascendancy, the forms moving up and out; a feature of much Baroque painting, but not really present in Rembrandt. It’s something that meant a lot to de Kooning, I’m sure. Early De Koonings; Dark Pond, Attic and Excavation, were recognized by Milton as surpassing art. It could not be otherwise, especially as Resnick’s wife, the painter Pat Passlof, had been de Kooning’s private student. But the personal history between the two artists was so complex and painful — very much recalling the relations between Braque and Picasso I might add— that discussing de Kooning with Resnick was always a loaded proposition.

In my opinion embracing Soutine represents a break from the art of the 1940’s. The immediate postwar period emits the odor of Surrealism, which means drawing and the imagination, and that includes significant aspects of Picasso. De Kooning was quite influenced by Soutine of course, but underneath it was Picasso and Synthetic Cubism, newly minted as it was. Milton was not nearly as oriented towards Picasso, but Picasso, Miro and Mondrian meant Modern art. Embracing Soutine meant embracing the not-really-modern. Yet Soutine didn’t draw, and neither did Milton. You see? Picasso and Matisse drew all the time. Try and imagine Matisse without the black line. Gorky and de Kooning drew all the time. And Pollock’s energies are all linear; exclusively so. It’s impossible to imagine their work without the function of line. Milton was heading somewhere else, so the turn towards Soutine was natural.

In 1946 Gorky told Milton and Bill, that at the last possible moment, before making a mark, he always put it in a spot that was different from his intention. How much did that mean to Gorky? Who knows? But to Milton it meant a great deal. Because removing the intention from the gesture renders one an observer rather than a doer. For Milton that posture was more artistic. The brain is limited; so is the imagination. It repeats; it seeks patterns; it can’t help but construct syllogisms. That propensity is sewn into our DNA, It’s something you see in animal behavior too; it protects us, extends our lives, but doesn’t serve well in art. This leads us into the last question you have.

PT: Resnick directly addressed the crux and the burden of abstract painting when he said: “I don’t think many people understand what it takes to paint a picture, say sixteen feet long, where there are no little people in it, no houses, no mountains. How do you paint a picture without all these things that make a picture?” Implicit in his question is an acknowledgement that the absence of something nameable to lean on creates an even stronger burden on the artist – an imperative to put something else, something unknown but of equal value into the painting – a fullness must be maintained.

GD: Why does the model for art have to be us? How many times do we have to make illustrations of our bodies and faces? It’s all such a bore. The turn towards abstraction is for good reason, and terrific artists have always been excited by abstract values, by relational values. But abstract art needed to be developed, and that required time. It required silence. Trying to put it together in a decade — I’m talking about the 1950’s now — was impossible, especially with all the hoopla, and the money flowing in, and the liquor being consumed. The studio became peripheral, and you end up with a lot of second-rate art. Of course there’s always been a lot of second-rate art. Nothing new there. We artists are human; we all have our weaknesses, and I’ve come to the conclusion that we all in the end do what we’re capable of, because so much comes into it besides ability, talent and intelligence. There’s capacity for feeling, patience, keenness of intuition, and most of all the ability to place demands on yourself that no outside person or institution will. To get that all in one package is problematic.

You talk about putting something of equal value into a painting to take the place of what used to be there. OK, fine. But how do you do it? By will power? By learnedness? By ingenuity? By being innovative? By mastering technology? I think instinctively we artists know that it’s not really those things. So what is it? It requires some sort of self-transformation; turning yourself into someone who can do that. For Milton that meant keeping things very basic, a daily confrontation between the artist and the medium — spreading color and oil — wetting it, scraping it, piercing it, flipping it, splaying it, moving it around on a surface, and always looking for where it would lock together. (As Delacroix says, “All of a piece, like the works of nature.”) Doing it again over years, over decades. Paint is always complex so it’s always different but it’s also recurrent, and gradually the mind is worn down, refashioned in such a way so that it becomes utterly responsive to what is happening in front of the eye.

There’s a fanatical edge to it. I don’t know of other artists that went at it like this. I’m not saying there aren’t. I don’t know them. It separates you from a normal existence; it’s a good way to vanish, really, because you’re involved in an activity that does not invite sympathy except for those who interested in that sort of thing.

Milton never cultivated a retinue. He had a talent for unnerving people, even those who wanted to help him. He had sympathy for Balzac’s Frenhoffer; the great artist who nobody’s heard of. I’m not even sure Milton would have understood or approved of the Resnick and Passlof Foundation. Like Kafka, he might have been content to let his artistic legacy vanish or burn. The foundation was Pat’s idea, it’s in her will. I have a feeling Milton would have said, “Oh Pat, it’s enough to have done it; Just let it go.”

Right now we’re all in a pickle. Devices are destroying our ability to think. Our mental stamina is shot to hell. Our embrasure of technical innovation is becoming increasingly desperate; we hope it will save us; save our fish, our bees, our water and our air. It’s so obvious we are moving towards catastrophe. People are turning back to religion and that’s because of fear. This idea of self-transformation, and then of transforming the culture, and I mean this in the widest possible sense, and finally the planet, is not so crazy. Just because we can do something doesn’t mean we should do it. Just because we can have something doesn’t mean we should have it. So I think this kind of art, in its enigmatic ability to coax feeling from seemingly nothing at all, holds a sort of message for us, despite it all.